Remembering the 1960s

Through Art and Activism

at the Bennington Museum

By Gayle Fee

An old joke goes: “If you can remember the ’60s, then you weren’t really there,” but two new exhibitions at the Bennington Museum, Fields of Change: 1960s Vermont and the accompanying Color Fields: 1960s Bennington Modernism, aim to assure that the tumultuous decade that brought political, social, and cultural upheaval to Vermont and the rest of the country is not forgotten.

“The exhibit is a retrospective—a look back—on the 50th anniversary of the end of the ’60s,” said museum curator Jamie Franklin. “A lot of the progressive things that make Vermont the wonderful place it is today are rooted in the culture of change that happened in the ’60s.”

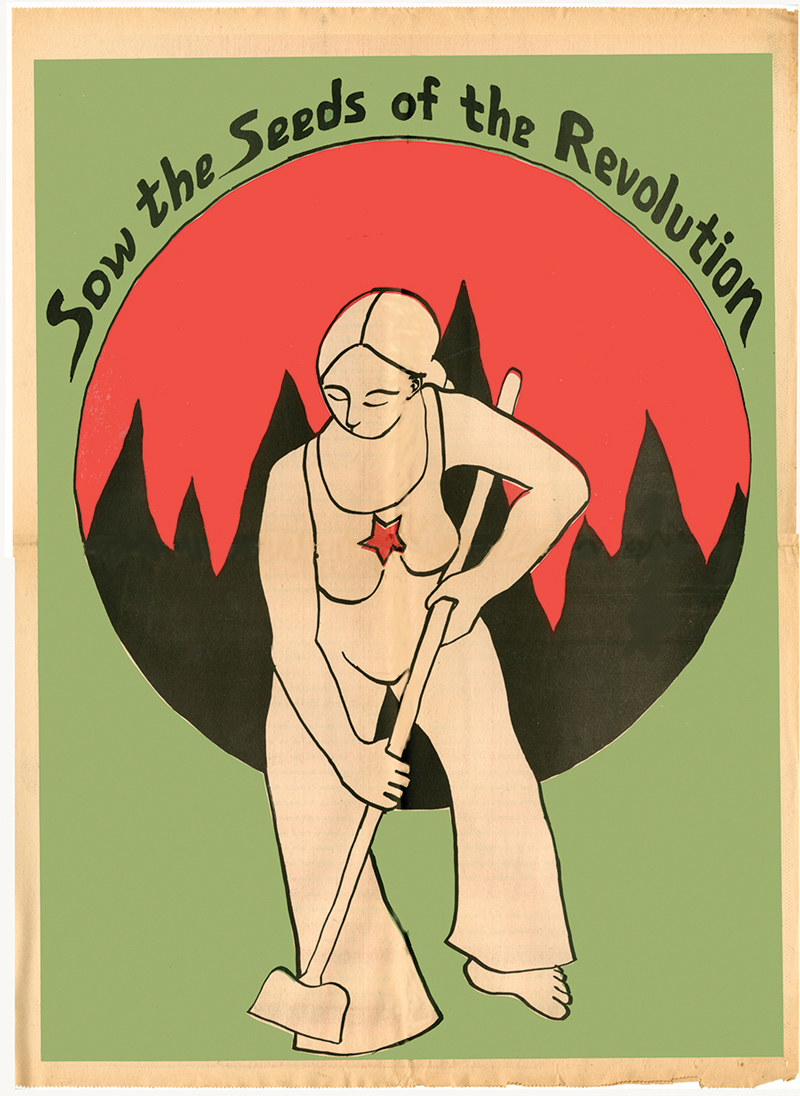

Fields of Change explores the influence of those events through photographs, archival documents, works of art, posters, fashion, crafts, and more. Its counterpart, Color Fields, examines the work of Bennington artists, whose radical experimentation with pared-down, color-based works reflected the dramatic cultural changes born during that decade of turmoil.

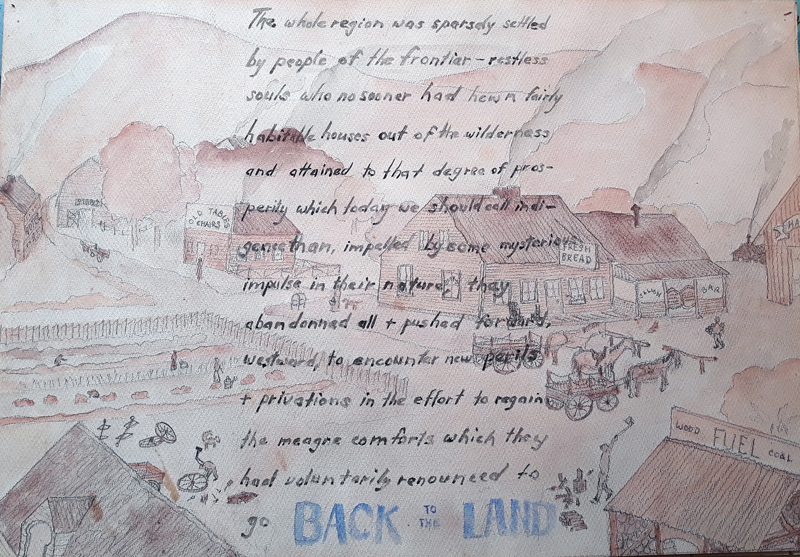

For a small rural area, Vermont was an epicenter for much of the radical changes seen in the 1960s. Fields of Change showcases many of the events that transformed the state from a longtime Republican stronghold to an epicenter for many progressive views. Political change began in Vermont with the 1962 election of Phil Hoff, the first Democratic governor in more than 100 years, followed by the court-ordered reapportionment that changed the makeup of the state House of Representatives, resulting in “a distinctly liberal shift in Montpelier,” Franklin said. At the same time, the construction of the interstate highway and the hippie Back-to- the-Land movement brought a lot of young progressive people to the state. “The people who came here with the idea to step back and live off the land were not all that different from traditional family farmers, even if their social and political ideas differed wildly,” Franklin said.

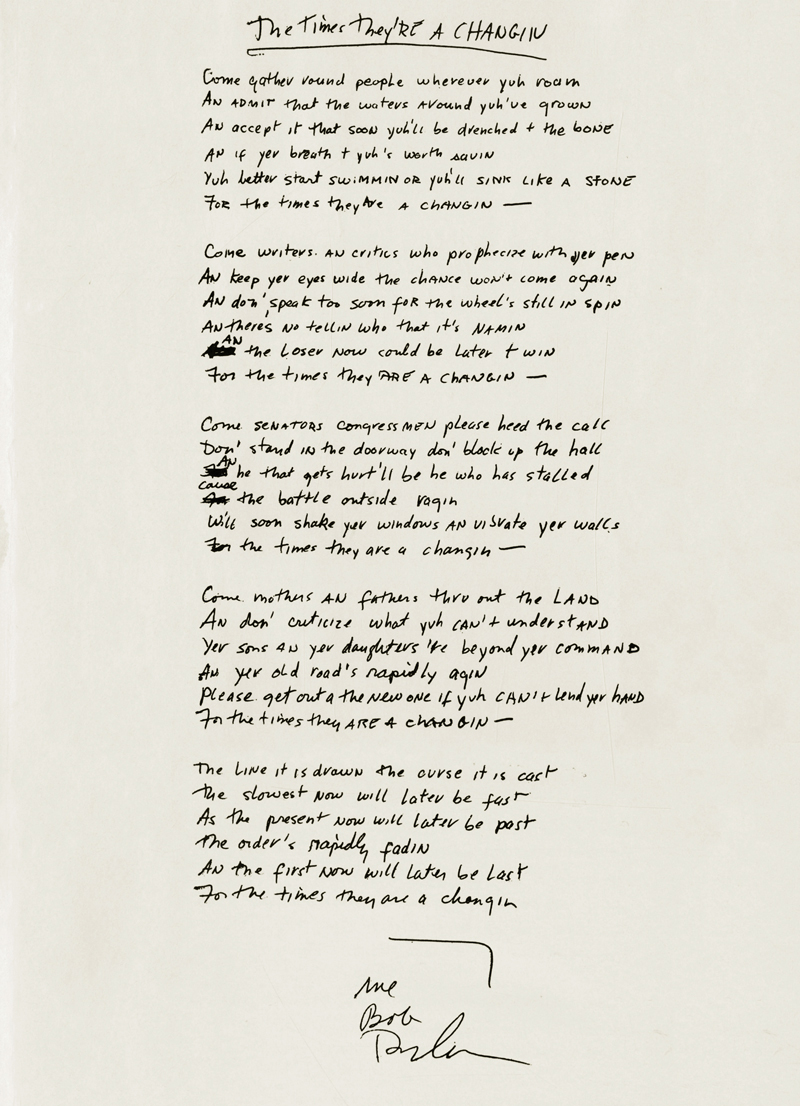

The exhibition includes photos and posters depicting Vietnam War protests organized by Bennington students juxtaposed with photos of the 1960 Bennington Battle Day parade float that featured men in military uniforms with what looked like an imitation nuclear warhead. Other highlights include Back to the Land, a watercolor by Tom Fels, one of the original members of the Vermont commune Total Loss Farm; puppets from the radical Bread and Puppet Theater; the lyrics to Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a Changin,’” which were first published in the Bennington College magazine SILO; a colorful pop-art dress by Vermont designer Tzaims Luksus; and photographs of billboards by then-Mount Anthony High School student David Wasco, now an Oscar-winning production designer, that were part of a school project on visual pollution that led to the Vermont billboard ban in 1968.

Greg Guma, a journalist, magazine editor, community organizer, and the author of several books including The People’s Republic: Vermont and the Sanders Revolution, supplied numerous photographs and much of the background information for the exhibition. Like many young, progressive activists and hippies, Guma moved to Vermont after graduating from college. “It was 1968 and I was fairly traumatized by what was going on during my final semester,” he said. “The war, the election of Nixon, the protests, the assassinations. Like a lot of people, I wanted to flee the violence and try to find better values in a less complicated environment.”

Guma got a job as a reporter and photographer at The Bennington Banner where he chronicled many of the historic changes taking place in the state. “I was one of only two reporters, so I was exposed to many aspects of society,” he said. “I watched the culture war unfold.”

While that war was unfolding on the political and social fronts, a group of artists who had gathered in and around Bennington College were revolutionizing abstract art, creating a new style of painting characterized by large fields of solid color that spread out beyond the edges of the canvas. Their pared-down, color-soaked works came to be known as Color Field. “The Color Field exhibit focuses on artists connected to Bennington College who were pushing the boundaries of radical experimentation,” Franklin said. Those artists include Pat Adams (one of the first women faculty members at Bennington College), sculptor Anthony Caro, painters Vincent Longo and Jules Olitski, former college art department director Paul Feeley, former Bennington students Helen Frankenthaler, Ruth Ann Fredenthal and Patricia Johanson, and former college trustee Kenneth Noland. The exhibition, according to the museum, situates “these artists and their work in the context of the dramatic cultural and social changes that came to define Vermont during this period, especially the counterculture and Back-to-the-Land movement.”

According to Franklin, most of the artists did not view their work as political, “but as an art historian, I am always interested in how art can echo the larger historical context in which it is made,” he said. “It’s interesting to think about the thematic issues that might bind history and art together. And while the artists might not necessarily be political, in that they weren’t creating art about Back-to-the-Land or the Vietnam War, they were radical experimenters.”

During the 1960s, Bennington College served as a rural epicenter for these artists and the outside world was beginning to take notice. Vogue magazine dubbed Feeley, Noland, Caro, and Olitski “The Green Mountain Boys” and their presence drew other prominent artists to the campus, including Jackson Pollock, Hans Hofmann, Adolph Gottlieb, Morris Louis, David Smith, and Barnett Newman.

“At the center of this group was Paul Feeley, who, as head of Bennington College’s art department created an atmosphere that buzzed with the energy of probing thoughtfulness and bold experimentation,” a museum writeup explains. “These artists were nurtured by the atmosphere of artistic inquiry cultivated at Bennington College and animated by its proximity to the art scene in New York City.”

But the movement was not all about the “Boys.” Bennington was, after all, an all-girls school at the time. Frankenthaler became an important artist in her own right after she began experimenting with stain technique, thinning her paint and applying it to unprimed canvas to create translucent layers of color that revealed the canvas surface. “She diluted the pigments until they were very liquidy and would throw them onto the canvas from a coffee can,” Franklin said. “The diluted paint would soak into the canvas until the color and canvas became one.”

Bennington Museum

Vermont State (from the Four Corners series), 1971

Francis R. Hewitt (1936–1992)

Dirt on linen, 72 x 72 inches

Collection of the Fleming Museum of Art, University of Vermont,

Gift of Karen Hewitt

The Color Field artists may have been abstract painters but much of their inspiration came from the Vermont landscape and the exhibit focuses on pieces that reflect that. They include Frankenthaler’s Cascade, a small but beautiful soak stain painting from 1966; an untitled 1962 work by her teacher, Paul Feeley, that is another example of soak stain technique; Olitski’s Twelfth Hope, a classic spray painting from 1969; and Via Light, a 1968 masterpiece by Noland who is considered one of the most significant proponents of Color Field. Tying Fields of Change and Color Fields exhibitions together are two paintings from Frank Hewitt’s Four Corners series. Hewitt bought a cabin in East Corinth, Vermont in 1965 and his 100 Acres is comprised of actual soil from the four corners of his farm, a classic nod to the Back-to-the-Land movement.

While the artists represented the bounds of abstraction, the counterculture experimented with new and exciting cultural, political, and social ideals. “The world was a complicated place in the ’60s,” Franklin said. “We are trying to show the complexity of that change—and how what happened in that decade affected rural Vermont.”

ALL THE DETAILS

Fields of Change is on view at the Bennington Museum

until Nov. 3.

The Color Fields exhibition runs through Dec. 30.

802-447-1571 or benningtonmuseum.org