A Name Synonymous with Southern Vermont Photography

My first introduction to Hubert Schriebl came the same way it does for most people who didn’t already know him from the early days of Stratton, or from conquering Stratton’s summit with him on his regular pre-dawn hikes to the top of the mountain, or from working with him on one of the resort’s marketing ventures.

It came about through photography, of course. I remember flipping through a copy of Stratton Magazine back in the late eighties and being blown away by the photos, all of them made by the same guy who seemed to have a vowel missing from the end of his name. What a shame about the typo, I recall thinking. One in particular grabbed me. It was a photo of a snowboarder in a competition, dropping downwards but in a time-lapse mode so that the shadow images of his mid-flight descent hovered over him as he busted a move to reveal the “Burton Air” name, sharp as a tack. I studied the picture for a long time, trying to figure out if it was a collage of several photos, or some way of exposing a single frame that achieved that effect. I certainly had no clue how to do that myself, and thought that if I ever had the chance, I should ask this genius Mr. Schriebl how he made that exposure—with a shutter speed fast enough to freeze the action but long enough to get the time lapse effect. No question, this fellow was way out of my league.

Years passed, and eventually my path began to cross with Hubert, as I came to know him, and each time I forgot to ask about the photo. There were too many other interesting things he always seemed to be up to in the present moment.

Mountain climbing, for one. Hubert is well known for his early morning hikes, which he does several times a week with whoever’s around and willing. If you’ve never tried hiking to the summit, well, all I can say is that it is just as much of a workout as it seems. I did it once—not with Hubert—and yes, you are soaked in sweat by the time you reach Hubert Haus at the summit, a short stem christie turn from the gondola drop off and named after you-know-who. Each time he completes a climb, Hubert carves a notch into the railing in front of the small chalet where he and his hiking companions relax after the summit walk.

But hiking to the top of Stratton is child’s play for Hubert, even as he crosses his milestone 80th year. All that mountaineering probably has a lot to do with why he’s still as vigorous and acute as someone half his age, but after having bagged some of the really challenging peaks in the Alps and the Himalayas, the 3,875 feet stroll up to the top of Stratton is probably less about the physical and more about the mental and spiritual. Plus, the light can be dramatic and there are some great photos to be had along the way.

But hiking to the top of Stratton is child’s play for Hubert, even as he crosses his milestone 80th year. All that mountaineering probably has a lot to do with why he’s still as vigorous and acute as someone half his age, but after having bagged some of the really challenging peaks in the Alps and the Himalayas, the 3,875 feet stroll up to the top of Stratton is probably less about the physical and more about the mental and spiritual. Plus, the light can be dramatic and there are some great photos to be had along the way.

Kimet Hand first met Hubert when he was a ski instructor at Stratton in 1965, and she was enrolled in one of his classes. He was already a well-known personality around the mountain, although not yet the “official” photographer of the mountain and had only arrived the previous year, at the invitation of Emo Henrich, then the ski school director at Stratton, and a legendary personality in his own right. Hubert was one of those people who seemed to know everybody and everybody knew him, she recalls.

“Hubert was just one of those people who connected all the dots,” she says. In addition to being a ski instructor, he also worked in the mountain’s marketing department, when she began working at the information booth in 1969. “He is ‘Mr. Stratton’—nobody else comes close to being the most well-known and most loved person at Stratton—no competition at all.”

“ He is ‘Mr. Stratton’— nobody else comes close to being the most well-known and most loved person at Stratton—no competition at all.”

—Kimet Hand

Hubert grew up in Pack, a small village in Austria, one of seven children. His father was a forester—sort of like a game warden in the U.S.—as well as a farmer. He never made it beyond grammar school—his help was needed on the farm. He became interested in leatherwork—taking a job at Innsbruck, a center for skiing in Austria; he learned how to make bridles and other leather gear needed for horses, beginning as an apprentice. He made very little money—bus fare for a trip back home was more than twice his weekly salary, he recalls. To get around, he and one of his brothers shared a bicycle—if they were both going in the same direction, they would take turns riding the bike while the other ran to keep up, he remembers.

“Growing up humble, you appreciate things more,” he says now over a cup of hot chocolate at the Spiral Press in Manchester. “You find out later it molds you, and what are your values.”

He looks back on those days in the early-to-mid-1950s as a wonderful time. Leatherwork became a passion, he says.

“I loved the job,” he says. “It was a lot of sewing leather. The toughest job was making leather belts for saw mills,” which had to be overlapped and sewn together precisely, he added.

He lived in a windowless room in Innsbruck barely large enough for a bed and a closet, his backpack stashed under the bed and a pair of skis leaning up against a wall. He skied as often as he could, even during lunch breaks from work.

“I got to meet a lot of people and made a lot of friends,” he says with a chuckle. “Living simple, and experiencing a lot.”

At Innsbruck he became a mountain guide and a certified ski instructor, and in 1959 was good enough to win a job as the ski coach for the Greek Olympic ski team. Yes, they have one, and yes, they have snow in the mountains of Greece. Hubert is mulling heading back there this spring, to climb Mt. Olympus—fans of Greek mythology will recall that was where the Delphic oracles were passed on from the gods to the mortals—not a bad way to celebrate turning 80.

At Innsbruck he became a mountain guide and a certified ski instructor, and in 1959 was good enough to win a job as the ski coach for the Greek Olympic ski team. Yes, they have one, and yes, they have snow in the mountains of Greece. Hubert is mulling heading back there this spring, to climb Mt. Olympus—fans of Greek mythology will recall that was where the Delphic oracles were passed on from the gods to the mortals—not a bad way to celebrate turning 80.

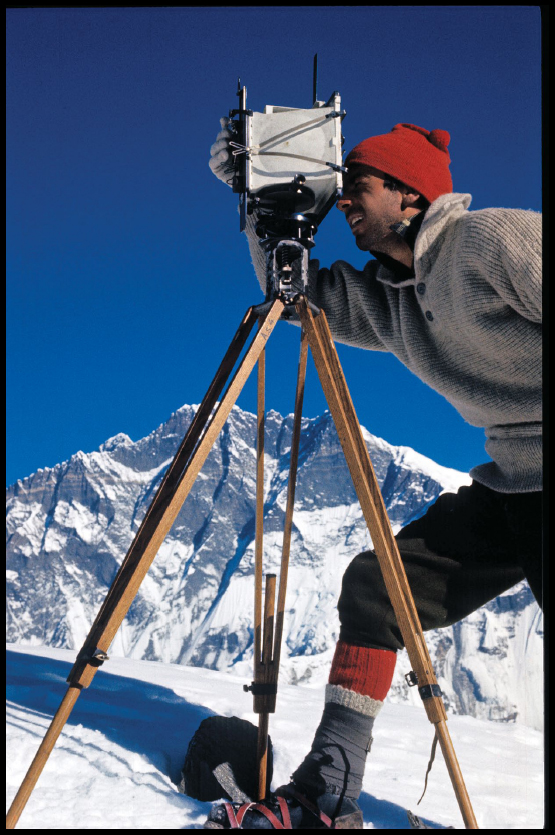

The following year it was off to the first of what would turn into four trips to the Himalayas during the 1960s and some memorable experiences at the world’s highest altitudes. Out of the mountain climbing came the emergence of his career as a photographer, he says.

An acquaintance had given him a camera that was somewhat less than fully reliable—it had a balky shutter and you had to be extra sure you had loaded the film correctly. But the vistas from the mountains were awe-inspiring.

By the time he was climbing in the Himalayas, he owned a Leica, a German-made camera that was considered the state of the art for the 35 mm film format at the time. It was his first “real” camera, and he paid it off slowly as the funds trickled in.

While in Innsbruck he crossed paths with Emo Henrich, who enticed him to come to the U.S. and work with him as a ski instructor in 1964.

“I came out of curiosity,” he says. “I went on the Himalaya expedition and when I came back I went to Innsbruck, changed my bags and came over here.”

Arriving at the bus stop in Manchester—then located where the Rite Aid store stands now on Main Street—his first experience of the town was slipping on a patch of ice and landing on his backside. But things began looking up quickly from there, he says now, laughing at the experience.

He saved enough money from his work as a ski instructor to purchase a used VW Beetle when he returned to Innsbruck later that spring. He met his wife, Wendy, after that first season in Stratton and they were married in 1967. The following year they moved to Stratton to stay as year-round residents.

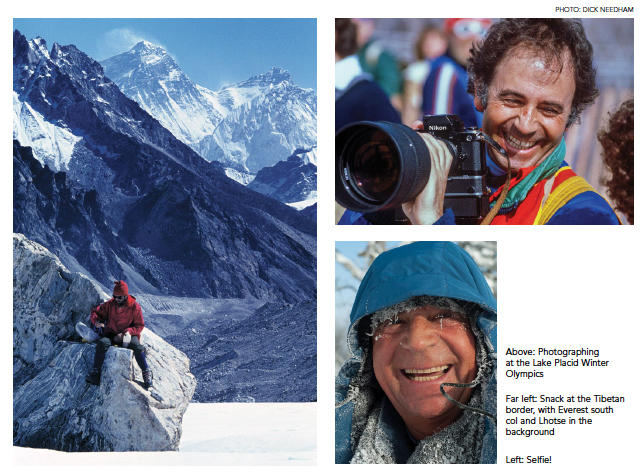

Hubert credits Ernst Haas, one of Austria’s foremost photographers ever, with being a large influence on the development of his “eye” and technique. Haas, frequently mentioned in the same breath as the other giants of 20th century photojournalism such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa and Elliott Erwitt, made his mark by bridging the gap between documentary photography and arresting creative work. Schriebl and Haas collaborated on several projects that led to his covering numerous major international sporting events, including four Winter Olympics and several World Cups. And through it all, Hubert’s talent continued to evolve.

Hubert’s enormous body of work eventually led to his winning the Paul Robbins Ski Journalism Award in 2009, bestowed by the Vermont Ski Museum.

Not that he started from a low baseline. Flipping through the pages of Schriebl’s book Stratton: The First 50 Years, one is struck by the dramatic imagery of ski racers as well as the snow-covered landscape pictured in the photos he took in the 1960s. Compositionally, they all draw the eye in, and turn what would, in lesser hands, be a mundane image into art. And it just keeps getting stronger from there, with his trademark style of crisp, perfectly exposed, frozen moments in time captured then on film, now digitally, not only of ski racers, but of other events that took place at the resort over the decades. His enormous body of work eventually led to his winning the Paul Robbins Ski Journalism Award in 2009, bestowed by the Vermont Ski Museum.

Lee Krohn, for many years Manchester’s planning director and an award-winning photographer as well, sums up Hubert’s talent as being something of a three-way street.

“One is his general attitude and approach—he brings a certain joie de vivre about working with people, and you don’t find that very often in photography,” Krohn says, adding that his joyful style is a skill, distinct from the other aspects of his craft. “He’s very skilled from a technical perspective; he’s got the eye for light and composition and he’s willing to work to get there at the right time of day.”

Along the way, Hubert has done many things for Stratton. In addition to being a general goodwill ambassador and official photographer both for the resort and Stratton Magazine, he ran the Stratton Arts Festival for nine years from 1979–86. And through it all, there was the mountain climbing, Kimet Hand says.

“People who never climbed before all of a sudden got climbing equipment and they climbed because they wanted to go with Hubert,” she says. “And you had to be there at 5 a.m. because that’s when Hubert leaves!”

Hang around with Hubert long enough and you’ll hear him refer to himself as a “dreamer,” dating all the way back to when he was a small boy growing up in the little village in Austria. The dreaming has carried him far, across a remarkable career that has taken him to the top tier of sports and skiing photography. And who can picture Stratton, when you close your eyes and visualize it in your mind, without one of Hubert’s pictures snapping into focus?

Perhaps his friend and mentor Ernst Haas put it best, and eerily, one suspects he could have been thinking about Hubert when he described his own approach to photography in an interview several decades ago.

“You become things,” he said. “You become an atmosphere, and if you become it, which means you incorporate it within you, you can also give it back. You can put this feeling into a picture. A painter can do it. And a musician can do it and I think a photographer can do it too, and that, I would call that dreaming with open eyes.”

Happy birthday, Hubert!

And by the way, thanks for explaining how you made that picture of the snowboarder. A multiplier lens, attached to the main camera lens, which breaks up the image, is the secret. But there’s skill to be brought into play too—you have to compose the photo in such a way to leave room for the ghost images created. Now I need to get one of those too. ◊

Andrew McKeever is a frequent contributor to Stratton Magazine.