STORY BY BENJAMIN LERNER

PHOTOGRAPHY & ART COURTESY TILTING AT WINDMILLS

A retrospective history of Tilting at Windmills’ first 50 years

Walking through the Tilting at Windmills art gallery in Manchester is a memorable and captivating experience. Inside, the walls are lined with gorgeous paintings. Finely crafted sculptures further enhance the inviting and elegant ambience, creating an atmosphere that beckons visitors to savor a refreshing moment of artistic exploration. Although Tilting at Windmills began as nothing more than a simple poster and frame shop, it has since carved a distinctive niche for itself as a treasured jewel of the Manchester arts community. As Tilting at Windmills celebrates its 50th anniversary, the gallery is in a better place than ever before. With a well-curated collection of artwork by well-renowned and internationally collected artists, it stands strong as one of New England’s largest commercial art galleries. Tilting at Windmills has come a long way from its humble beginnings, but the majority of frames that hold the paintings are still lovingly hand-cut in the upstairs workshop. The frames serve as a perfect illustrative metaphor for the decades of diligent and dedicated stewardship that has led to Tilting at Windmills’ sustained success. Truly timeless art may come from moments of transcendental inspiration, but it’s the work done behind the scenes that holds everything together.

Early Years

When Sean Hunt first visited Southern Vermont in the spring of 1971, the serene and tranquil beauty of the Green Mountain State made a lasting impression on him. At the time, Hunt was working towards his graduate degree at the Berklee College of Music in Boston. After returning to Boston, Hunt began to contemplate taking a summer job in Vermont. He heard from a friend that the owners of the Avalanche Motel in Manchester were looking for a musician to play five nights a week at their bar, so he returned to Manchester to audition for the job. Hunt won over the Avalanche Motel’s owners with an inspired performance and spent that summer in Manchester. Hunt made a lasting connection with the Avalanche’s bartender, Tom Simmons, who would end up playing a pivotal role in the founding of Tilting at Windmills.

That fall, Simmons visited Hunt in Boston. One day, the two went to a poster shop together. Although they were delighted with the vast array of striking poster options that they found at the store, they were even more impressed by the fact that the store offered to dry mount the posters on foam board for their customers.

After Hunt and Simmons left the shop, they went to a nearby oyster bar to get lunch together. During their lunch, Simmons postulated that a poster shop that offered dry mounting services would be very successful in Manchester. Although Hunt was initially skeptical, he began to open up to the idea as the conversation continued. Towards the end of the discussion, they began to draw up serious plans to bring their poster framing operation into reality. When Hunt and Simmons were deciding what they would name their shop, Simmons turned to a poster he had purchased earlier for inspiration. The poster featured a Picasso painting of Don Quixote’s silhouette, which gave Simmons the idea to call the poster shop “Picasso.” Hunt was also inspired by the Picasso poster, but he had a different inclination. He countered with, “No – we should call it ‘Tilting at Windmills,’” a reference to the archaic English idiom that referenced Miguel Cervantes’ 17th century literary classic, Don Quixote.

In the months that followed their lunch in Boston, Hunt and Simmons pooled their resources, rented a space from Bill and Cecil Lowery on Main Street in Manchester, and opened Tilting at Windmills to the public on December 7, 1971. When Hunt and Simmons first opened the business, all they had was a dry mounting press, a few boxes of foam board, an initial order of posters, and a shared ambitious mindset. As the store began to build its clientele base, Hunt bought out Simmons’ share of the business and purchased the building that they had been renting from its owner. In the years that followed, Hunt welcomed his first daughter Hileary with his wife, Ginger, and began to expand his services to include traditional non-foam framing. Early on, he purchased pre-cut mats, frames, and glass from a wholesale framing operation in Chelsea, Massachusetts. Although Hunt was starting to draw a noticeable profit from his expanded framing operation, he quickly became tired of driving back and forth from Massachusetts with the pre-cut frames. He knew that he had to learn how to cut frames himself in order to continue to grow his business. Over the next several years, he began to develop his framing skills and built a small frame-cutting workshop in the upstairs space of his building. The business continued to flourish while Hunt honed his craft, and Hunt began to develop relationships with area artists. One talented artist from Gloversville, New York, Gunter Korus (1926-2021), would end up playing an integral role in shaping the future trajectory of Tilting at Windmills.

It was 1975 when Korus arrived at Tilting at Windmills in a Volkswagen bus that was filled entirely with paintings. When Hunt bought one of Korus’ small still life pieces on that day, it started a long and lucrative business relationship. Over the next several decades, Korus established an exclusive consignment arrangement with Tilting at Windmills. This symbiotic partnership helped Korus build his reputation as an artist and also helped Tilting at Windmills gain traction in the art world. In the years that followed, Tilting at Windmills’ roster of artists expanded to include other master artists such as Hale Johnson and Gerald Lubeck, who also forged exclusive partnerships with the gallery. According to Tilting at Windmills’ current owner Terry Lindsey, Korus was best known for his stunning three-dimensional realism in landscapes and still life works. Gerald Lubeck (1942-2019) was a versatile artist who lived in Vermont and painted scenes from a variety of regions. He also painted scenes with livestock and plants from different environments. Hale Johnson specializes in highly-detailed oil paintings of old architectural structures, as well as rustic paintings of rusty roofs, rough boards, and farm antiques. Together, the works of Korus, Lubeck, and Johnson contributed greatly to the overall success of Tilting at Windmills as a business throughout all of its subsequent stages.

When Ben Hauben acquired several properties in Manchester and brought outlet stores to the area in the early 1980s, the Shires region entered a new era of collective business prosperity. Hunt was able to capitalize on the new Southern Vermont tourism surge. He jumped at the chance to increase the quality of the artworks he was showcasing at Tilting at Windmills and decided to take new stylistic risks with his framing. After Gunter Korus’ works sold out several years in a row at the International Art Exposition in New York City, Tilting at Windmills earned a reputation as one of the preeminent art galleries in the Northeastern region of the United States.

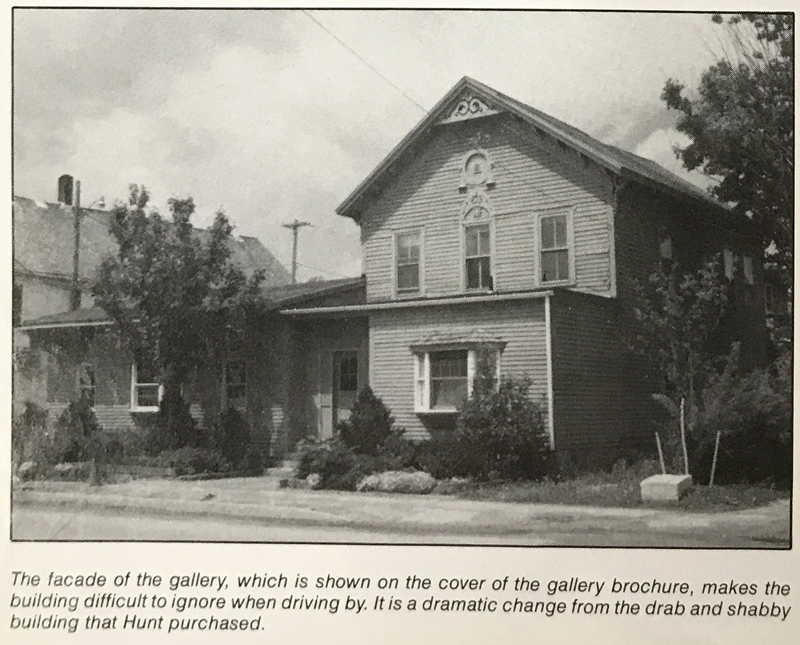

Unfortunately, the era that accompanied Manchester’s newfound retail boom also came with a downside. The streets became so heavily trafficked that patrons were unable to find parking for the gallery. At that point, Hunt realized that Tilting at Windmills had become a destination in itself for his growing clientele base. He set out to find a location that was far enough away from Manchester’s bustling town center to avoid the traffic congestion, but still close enough that visiting tourists could still easily find their way there. In the midst of his search for a new location, Hunt reached out to his friend Kim Kimball in 1987, who pointed out a building on Highland Avenue off of Depot Street. According to Kimball, the building had once served as the home of a restaurant known as “The Chicken Shack,” and later as a local health clinic. When Hunt walked through the doors, he saw that the downstairs interior was filled with cubicles. Although Hunt knew that the space needed a complete overhaul, he was confident that he could make it happen. In the 15 years that he had spent at Tilting at Windmills’ original location, he had become well-versed in design and renovation through a series of small refurbishment projects. Once he made the final decision to acquire the new property, he began to draw plans for a comprehensive renovation. The redesign project marked the end of Tilting at Windmills’ original era and allowed the gallery to transition into a place where it could gracefully come of age and cement itself as one of Southern Vermont’s most highly-regarded artistic landmarks.

Renovation and Redesign

Hunt purchased the building and began renovations in September 1988. He devised new floor plans for the first and second floors with the help of architect Mark McManus. The entire structure was then gutted, and the exterior was stripped down to its bare bones. The standard-size house windows from the old building were replaced with a series of custom windows, including large display windows that allowed potential patrons to see artwork from the street. In the display windows, suspended panels were affixed to vertical brass rods, allowing the artworks on both sides of the panel to be easily rotated and shown to patrons inside. In addition, a series of strategically-placed “eyebrow” windows allowed natural light to spread throughout the gallery and also provided much-needed ventilation. The entire building was reinsulated, the electrical and air conditioning systems were reconfigured, and a series of new fixtures and a new roof were installed. The renovation work was overseen by Fairholm Builders of Dorset, Vermont.

The staircase at the back of the building was also moved and enclosed, and the interior walls were redone. Inside, a network of open spaces and standalone panels was constructed, where individual works of art could be deliberately placed to increase visibility. In the center of the gallery, a semicircular island was constructed, complete with office workstation and a glass-coated wrapping counter. The cabinets in the island were designed by celebrated Dorset-based artisan woodworker Dan Mosheim. The island was deliberately designed to allow the gallery’s proprietor to be able to watch patrons throughout the gallery, while still giving the visiting customers space to explore the artworks and maintain their sense of privacy. Adjustable track lighting and recessed lighting fixtures were installed, providing both ambient and directed light to the gallery.

On the second floor, Hunt built a fully-operational frame shop. Every fixture, cabinet and shelf in the frame shop was designed to ensure maximum spatial efficiency. Each workstation in the frame shop featured built-in cabinets with multiple storage shelves. Additional cabinets for prints and artworks allowed for organized storage, including a specialized area for scrapped pieces of matboard. One room in the frame shop was designated as the “dirty room,” where glass and frames were cut. The “dirty room” also featured an air compressor to power the shop’s tools. The enclosed staircase led directly into the workshop, enabling the seamless deliveries of artworks directly to the framing shop and storage area. All in all, the renovation took six months to finish and was completed in March of 1989. In June 1990, Tilting at Windmills won an Award of Excellence from DECOR Magazine for Gallery and Frame Shop Design. Hunt’s hard work paid off in more ways than one, and he made a lasting mark on the Manchester arts scene.

The Story Continues

During the course of the renovation, Hunt decided that he wanted to step away from the gallery and began looking for a suitable new owner to take over and continue the work that he had started. Hunt met Suzan Claytor while he was teaching an advanced mat cutting workshop in Keene, New Hampshire. Over the course of a conversation between Hunt and Claytor, Hunt revealed that he was thinking about selling his business. Claytor and her husband, Harry, were interested in buying an established and lucrative gallery and framing business, so they drove to Manchester to see the property first-hand. After several months of negotiations, Hunt sold the gallery to Suzan and Harry in July of 1990. Tilting at Windmills went on to reach new all-time highs in terms of sales, and the Claytors continued to build on the gallery’s already-stellar reputation by establishing new relationships with fine artists and marketing the gallery to new audiences.

By coincidence, the Claytors met a talented local artist named Terry Lindsey, who had moved down from Middlebury to Manchester several years earlier. Lindsey had a strong desire to learn how to frame, and she began working for the Claytors at the gallery for two days a week. “I learned a lot about framing and what it takes to run an art gallery during that time,” says Lindsey. “I ended up showing my work at Tilting at Windmills, and it was a fantastic experience.” After working at Tilting at Windmills for several years, Terry branched out on her own and opened up the Equidae Gallery in Saratoga Springs, New York, which was open every summer for the entire racing season from 1999 to 2013. The Equidae Gallery was dedicated to showcasing equine art and featured a variety of captivating pieces from artists such as Kathleen Friedenberg, Jenny Horstman, and Jaime Corum.

In 2012, the Claytors decided that they wanted to sell the gallery and move to Florida. It was then that Lindsey offered to purchase the gallery. Since becoming Tilting at Windmills’ new owner in 2013, Lindsey has gone above and beyond to expand and diversify its offerings, while still maintaining relationships with the artists that defined the gallery’s initial upward trajectory. One of those artists is the late Gunter Korus, who passed away in August 2021. A comprehensive show celebrating Gunter Korus’ life work will show at the gallery from October through December 2021. Highlights include his magnificent “Cut Crystal” oil painting, which is a personal favorite of Lindsey’s. “Over the years, Gunter experimented with a variety of styles and mediums, but his oil paintings really showcase the best aspects of his artistry. His realistic paintings are beyond realism or photographic – they are a truly three-dimensional. You can really sense the textures in them. The way that the light reflects off the glassware is just phenomenal. Each subject gives you the sense that you can pick it right out of the painting. He is, no doubt, a master.”

Another artist of note who is shown in the gallery is Michael Fratrich. His paintings feature epic depictions of rustic landscapes with vivid colors, creating a contemporary edge to his expression. Several abstract paintings by Chandler Kissell convey a sense of energetic intensity, and a marble egg-shaped statue by Jane Armstrong (made of Southern Vermont marble) stands on a pedestal in an intimate corner.

Other highlights from Tilting’s current collection of over 50 talented artists include pastel paintings by Barbara Groff and landscape paintings from up-and-coming young artist Andrew Orr. According to Lindsey, “His paintings seem to sell out faster than they are hung on the wall.” In addition, the gallery features an exclusive collection of paintings by long-established Tilting at Windmills favorite Gerald Lubeck, scrap metal equine sculptures by Jenny Horstman, expressive scenic paintings by X. Song Jiang and Omar Malva, nature photographs by award-winning photographer Ashleigh Scully, landscape paintings that blur the line between abstraction and realism by Doug Smith, humorous and whimsical bronze animal sculptures by Susan Read Cronin, a large collection of fun and accessible paintings by Stuart Dunkel, and a small number of expertly painted and sculpted pieces by Lindsey, herself, to name a few. (The aforementioned artists are only a few names from the full roster of artists represented at Tilting at Windmills.)

“A favorite piece of mine in the gallery is a painting of my dog, Wren,” says Lindsey. “It’s not for sale, but it makes me feel good to look at it, because I caught her ‘look.’ For me, that’s what art should do! I think it should evoke the emotions that you want to feel.” In the back of the gallery, a painting that Lindsey completed during the onset of the COVID pandemic is situated prominently on a wall in the middle of a well-lit room. The painting is entitled, “A FEW GOOD WORDS.” According to Lindsey, she created the painting as a visual testament to the power of honesty, hope, inspiration, creativity, perseverance, and more. “I started the painting at a time when everyone was feeling cut off from human connection. Every night, I would go home and paint. This particular piece was a totally different expression. It served as a form of personal expressive therapy at the time and continues to remind me of where I want my thinking to be when I look at it. We all need something in us that satisfies that human instinct for meaning, goodness, honesty and togetherness. Everyone responds differently to the paintings in the gallery. They attach their own meanings and interpretations. I think that’s the way it should be. It should be a personal experience. Art allows us to express and communicate with one another in a way that words might not be able to.” Lindsey has strong feelings regarding the importance of presentation. She feels that a frame can make all the difference in terms of how a timeless artwork is displayed and that a gallery’s overall presentation should be cohesive and balanced. Lindsey is grateful for the help that her husband, Al, has provided to her. “I am continually spoiled by my husband, who frequently helps me move the heavy pieces when installations need readjusting.” As Lindsey moves forward with her work at Tilting at Windmills, she feels a deep sense of responsibility towards the artists that she represents. “It’s up to me to make sure that the artists’ works are showcased in the way that presents them at their best. Being an artist myself, I have a great deal of empathy for the other artists’ efforts. It is very fulfilling to see a visitor become smitten with a painting or sculpture! The passion for art is not necessarily a need like food and shelter. However, it is a need that feeds our emotional happiness and pleasure. It can temporarily transport us. What fuels this need is a mystery, but when a piece of art speaks to you and you cannot rid it from your mind, you have found a new, devoted friend for life. Hopefully, you will take that friend home!”