By Silvia Cassano

Photographs By Hubert Schriebl

Atop the tallest mountain in Southern Vermont some sunny day you may find yourself at the Stratton Mountain fire tower, perched 55 feet high at 3,936 feet above sea level. Here you scan out upon a 360-degree view of the most contiguous forest and wilderness areas in all of Vermont. If you are fortunate, you can see the Adirondacks, New Hampshire’s White Mountains, and Mount Greylock in Massachusetts. What is unique about this view is that you are on the oldest long distance hiking path in the United States, the Long Trail (L.T.). You are also standing on the longest, skinniest national park in the United States, the first such designation of its kind, the Appalachian National Scenic Trail.

The 272-mile Long Trail, which links the peaks of Vermont’s Green Mountains starts at the Massachusetts border and ends at the Canadian border at Journey’s End. The Appalachian Trail (A.T.) starts at Springer Mt. in Georgia and ends at Mount Katahdin in Millinocket, Maine. They are aligned for approximately 150 miles from the Massachusetts border to the “Maine junction,” just north of Route 4 in Killington. The Green Mountain Club (GMC) and its volunteers maintain the Long Trail and its side trails. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) works with the Green Mountain Club and the National Park Service to preserve and manage the Appalachian Trail.

The preservation and stewardship of these trails has become increasing vital to their well-being and longevity. Thru-hiker traffic has increased each year in the past decade, a 9-percent increase from 2014 to 2015 alone. However, despite the increased popularity of thru-hiking, the highest use of the A.T. and L.T. is actually from day hikers, section hikers, or weekend backpackers. Higher use has physical and social impact on parts of the trail that haven’t been relocated due to either terrain, lack of funding, or people hiking during more sensitive times when the trail may be too wet. There have been issues of overcrowding, a higher volume of human waste, and an increase in unprepared hikers. ATC encourages people to voluntarily register for their hike and recommends hiking it differently these days by “flipflopping” and starting midpoint in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia or elsewhere to spread out the use.

The busiest overnight site on the Long Trail is the Stratton Pond campsite and shelter. The trail in the Manchester/Stratton area spans about 23 miles from Stratton-Arlington Road to Mad Tom Notch Road, with the summits of both Stratton and Bromley being accessible by gondola or chairlift.

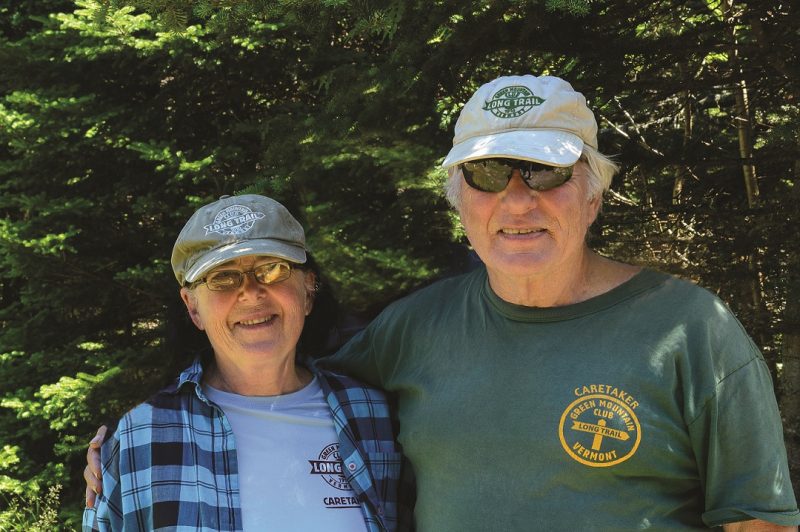

Hugh and Jeanne Joudry have deep roots on the summit of Stratton Mountain and have been the trail’s caretakers for the last 50 years. Hugh and Jeanne were hired in 1968 to be fire lookouts for the state of Vermont. Back then the fire tower lookouts “were all hermits” seeking reprieve from the late ’60s, says Jeanne. During the 1980s, when planes scouted fires, the Joudrys lived and worked in Brattleboro and Putney, and later moved to New York. They returned to Stratton Mountain in 1996, as Stratton Mountain Caretakers for the Green Mountain Club when staff was needed to educate the public on stewardship and proper hiking etiquette while on the Long Trail and the summit of Stratton.

When speaking of their caretaking era where visitors were sparse, to the “hiker revolution” of the 1970s to now, Hugh indicates, “now people come up and I have to show them where they get the best cell phone reception. We now get more distance, rate, and time questions. It went from these long, infinite pauses like you felt you were in a Buddhist monastery, to a highly interactive exchange with visitors.” “We try to educate hikers and visitors however we can,” Jeanne adds, “we tell people interesting things about the vegetation. How the balsam trees knit together, and that this is a 100-year regenerative forest.”

For many, the summit of Stratton Mountain would not be complete without a chat with the couple. Hugh and Jeanne estimate that each season they talk to roughly 7,000 people at the summit, with 70 percent of them arriving on the gondola. The Joudrys agree that with the increasing popularity of hiking, people need to be more aware of giving back, being prepared, and taking more time to be considerate of the mountain environment and others. “We try to tell people what they can do,” Hugh expresses. “We have three types of hikers to speak to. The A.T. hikers are different from the L.T. hikers, and these groups differ a great deal from the tourists off the gondola.”

Mike Debonis, executive director of the GMC, brings to light that, “the history of the Long Trail is as much about people as it is a footpath. Hugh and Jeanne’s own story is shaped by the trail and mountain that they have come to call home for so many decades. The fact that they are able to share their knowledge and passion of the trail with visitors adds a richness to the hiking experience that is unparalleled elsewhere.”

“The fact that these two trails are one in Southern Vermont, and that there are passionate stewards like the Joudrys whose time at the summit of Stratton developed into a lifetime of stewardship, caring for this place, the trail, and its travelers are invaluable,” chimes in Cheryl Byrne, a longtime friend of the Joudrys and a former GMC southern field coordinator.

Hugh gestures as he would while showing A.T. thru-hikers the view from the fire tower. “That’s where you’re coming from, it’s very philosophical, and that’s where you’re going. It’s a metaphor for a lot of things. Sometimes they reach the 1,600-mile mark; they’re beat. It’s become a special event for them to have a conversation.”

“We are very content doing what we do,” Jeanne smiles. “Very spiritual experiences on the mountain,” Hugh adds. “We’d never be who we are if we hadn’t done this. I don’t know what we’d be,” Jeanne says as she takes a casual sip of her tea, glancing at Hugh, nodding in agreement. The Joudrys use their slower off-season to create their art and to recharge and rest from an active and busy season of caretaking.

Jeanne earned a BFA in fine arts and graphic design from SUNY Buffalo and considers herself a painter and likes working in acrylic and oil pastels.

Hugh is a sculptor, writer, occasional playwright, philosopher, and by trade, a mathematician. He has journals detailing the weather for the past 50 years and is deeply concerned with the trends he is seeing in changes in precipitation. He developed his art over time, specializing in sculptures utilizing wood to create forms, many mythical and totem-like, that bring out the unique shape of the wood he has chosen to carve. His sculptures have been on display at Wanderlust at Stratton every year. He creates his sculptures in winter either in an unheated workshop at their home or in a wall tent. He takes breaks often to warm up. The rest of his winter is occupied by teaching math at Mount Snow Academy in West Dover, Vermont, where he is inspired by the motivation of his students.

Hugh and Jeanne’s work has been displayed at the Southern Vermont Arts Center in Manchester, Vermont.

Appalachian Trail Community™ Designation

After much campaigning by several local outdoor advocates and business owners, in mid-March, the ATC Regional Partnership Committee voted to approve Manchester as a Designated Appalachian Trail Community™. This program established by the ATC recognizes communities that promote and protect the A.T. and are neighborly to those who trod the trail. This makes Manchester the second designated A.T. Community™ in Vermont next to Norwich. Marge Fish, the Green Mountain Club Manchester Section President who for decades has been deeply involved with the GMC, believes that there is the need for more awareness in the community. Fish believes this designation may help garner more community support and volunteerism to support the A.T./L.T.

Anne Houser, owner of The Mountain Goat, helped to spearhead the Manchester A.T. Community™ designation, saying, “we already have so many hiker-friendly businesses in town and people come here to get outdoors, so we want to build more community around the trail and show hikers we support them.”

Other local initiatives include raising funds to rebuild the Bromley Mountain observation tower that was torn down in 2012. Bromley is a popular day hike because “a short walk yields a great view,” explains Fish. They have raised $50,000 toward the project, but $250,000 still needs to be raised to re-establish the panoramic view.

In addition to leading trail work projects with other Green Mountain Club volunteers, Fish has worked with local school groups seeking service projects on the trail. The Mountain School at Winhall once had a 5th/6th grade class do a unit on the Long Trail encompassing history, geology, geography, and all aspects of hike planning and because of this, the school has been performing service projects every spring and fall for the past 12 years. Volunteer work is critical to the mission, success, and future of both trails. For example, volunteers on the A.T. in 2015 put in more than 250,000 hours of work on the trail improving its drainage and alignment, overnight sites, corridor monitoring and maintenance, habitat improvements, rare plant monitoring, and so much more.

This sense of stewardship is common among those very passionate about the A.T. and L.T. When asked why she is so involved with the management of the Long Trail, Fish frankly states, “Well, I hike. If you hike you want to give back. At least I do.”

“A lot of people come up to hike, which is great. For the trail to be useable it needs more people doing the sweat equity work and making the donations to help pay for the professional trail crews. In a way, trail work is a work of art…. There’s a lot of artistry when you have to move a rock that’s 300 to 400 pounds,” Fish stresses. “There is an art to properly brushing in a bootleg campsite or clearing a waterbar.”

A Bit of Background

The Long Trail was conceived in 1909 by James P. Taylor, while camping out in his tent in the rain and viewing Stratton Mountain’s summit. Taylor, the assistant headmaster at Vermont Academy, often took his students out for treks and dreamt of a way to link Vermont’s Green Mountain peaks together with a trail. His vision became a reality with the formation of the Green Mountain Club in 1910. Work on the new Long Trail began shortly after with the final leg being completed in 1930.

It was in 1921 that forester and regional planner Benton MacKaye published his vision for another long distance hiking trail, the “Appalachian Skyline” that would travel across Appalachian Mountains to serve as a way for people to escape the hustle and bustle of modern civilization and to connect with nature. MacKaye first hiked a route from Haystack in Southern Vermont over Stratton and to Mount Mansfield in 1900, and again later once the Long Trail was established. Legend has it that he solidified his vision while atop the original Stratton Mountain fire tower, which was erected in 1914.

The Long Trail route in the Stratton Mountain area, as in other parts of Vermont, has seen several relocations throughout the years. There have been many instances where it did not cross over the actual summit of Stratton Mountain. Catastrophic fires were more common in the early 1900s due to poor logging practices and an increase in logging activity. In 1904, an established network of town forest fire wardens was put into place, but that wasn’t enough. In 1910, legislation called for fire patrol and state-employed watchmen to look for fires at watch stations built on private land. The current fire tower was rebuilt in 1934 and is on the National Historic Record. The Stratton Mountain fire tower was actively used as a fire-monitoring station until 1984. In 1987, the U.S. Forest Service and the GMC had chosen to re-route the A.T./L.T. from Stratton Pond northward up the southwest side of Stratton to the summit and fire tower, and then down the northwest side to follow its original route. The role of the fire watch had been eliminated but remains a unique visitors destination.

The Leave No Trace Seven Principles

Trail-maintaining clubs and nonprofit organizations are worried that their volunteer base and membership are aging and are not diverse enough. The ATC’s New England regional director, Hawk, Metheny, attributes much of the success of the A.T. to the “thousands of dedicated volunteers who put Benton MacKaye’s vision on the ground. We have much to be grateful for with the A.T. as a world-class hiking destination on a protected land base. Both that vision and need for volunteerism are as important now as they were nearly 100 years ago to ensure a sustainable trail well into the future.”

Leave No Trace Principles are land-stewardship ethics we can use in front country (town/city park or trail system, town forest, and public recreation spaces) and backcountry sites to help provide a sustainable way to avoid human-created impacts so others can enjoy the natural world just as you did. The following are a small selection from the Leave No Trace Seven Principles. © 1999 by the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics: www.lnt.org that you can apply to your next hike on the A.T./L.T.:

Plan Ahead and Prepare

- Know the regulations and special concerns for the area you’ll visit.

- Prepare for extreme weather, hazards, and emergencies.

- Schedule your trip to avoid times of high use.

- If hiking in a large group (20 people suggested max), hike in smaller groups (3-4 people). On alpine summits or designated Wilderness areas, limit a day-hike group to 10 people including leaders. Check the Green Mountain Club’s Group Hiking Page for more information.

Travel and Camp on Durable Surfaces

- Durable surfaces include established trails and campsites, rock, gravel, dry grasses or snow.

- Protect riparian areas by camping at least 200 feet from lakes and streams.

- In popular areas:

• Concentrate use on existing trails and campsites.

• Walk single file in the middle of the trail, even when wet or muddy.

• Keep campsites small. Focus activity in areas where vegetation is absent.

Dispose of Waste Properly

- Pack it in, pack it out. Inspect your campsite and rest areas for trash or spilled foods. Pack out all trash, leftover food and litter.

- Deposit solid human waste in catholes dug 6 to 8 inches deep, at least 200 feet from water, camp and trails. Cover and disguise the cathole when finished.

- Pack out toilet paper and hygiene products.

Leave What You Find

- Preserve the past: examine, but do not touch cultural or historic structures and artifacts.

- Leave rocks, plants and other natural objects as you find them.

- Avoid introducing or transporting non-native species.

Minimize Campfire Impacts

- Campfires can cause lasting impacts to the backcountry. Use a lightweight stove for cooking and enjoy a candle lantern for light.

- Where fires are permitted, use established fire rings, fire pans, or mound fires.

Respect Wildlife

- Observe wildlife from a distance. Do not follow or approach them.

- Never feed animals. Feeding wildlife damages their health, alters natural behaviors, and exposes them to predators and other dangers.

- Protect wildlife and your food by storing rations and trash securely. Control pets at all times, or leave them at home.

- Avoid wildlife during sensitive times: mating, nesting, raising young, or winter.

Be Considerate of Other Visitors

- Respect other visitors and protect the quality of their experience.

- Be courteous. Yield to other users on the trail.

- Take breaks and camp away from trails and other visitors.

- Let nature’s sounds prevail. Avoid loud voices and noises.

Read and watch short videos about Leave No Trace outdoor ethics specific to the Appalachian Trail and applicable to the Long Trail at www.appalachiantrail.org and www.lnt.org.