It was one of those late summer Vermont days with the sky very high, utterly clear, and blindingly blue. The temperature was somewhere between ideal and perfect. There was no humidity and only the slightest suggestion of wind. In another age, the day would have been called “heavenly.”

Great, certainly, for hunting rattlesnakes. Timber rattlesnakes, to be precise. And to find them in Vermont, you really do have to hunt. There are so few of them that they qualify as “endangered,” and can be found in only a very few, very small, very specific areas. Doug Blodgett, a biologist with the Vermont Department of Natural Resources, had agreed to let me accompany him to one of the these rattlesnake habitats— the one with the largest, though still small, population of snakes. But I had to promise to keep the location secret. Certainly not to write about it.

Great, certainly, for hunting rattlesnakes. Timber rattlesnakes, to be precise. And to find them in Vermont, you really do have to hunt. There are so few of them that they qualify as “endangered,” and can be found in only a very few, very small, very specific areas. Doug Blodgett, a biologist with the Vermont Department of Natural Resources, had agreed to let me accompany him to one of the these rattlesnake habitats— the one with the largest, though still small, population of snakes. But I had to promise to keep the location secret. Certainly not to write about it.

“We’d get people coming to find the snakes,” he said. “And we don’t want that.”

“Find them for what?” I said.

“Oh, you know. To catch them. Keep them in a terrarium of some kind.”

Yes, I thought. That would make an interesting conversation piece for when friends dropped by for a glass of wine and a bit of cheese.

“And, you know, maybe to kill them for the skin.”

Yes, again. Nice wall decoration. Something to hang next to the New York Jets poster.

“Or just to kill them. Some people feel that way about snakes.”

Indeed. The entwined history of humans and snakes is not one of happy co-existence. Perhaps it has something to do with that unpleasantness in the Garden. So we associate snakes with sin of the original kind. And, then, the bite of a serpent can kill. Not the bite of all serpents. But some of them, certainly, including the Timber Rattlesnake which is used, in fact, in those religious ceremonies where people handle snakes as a test of faith, believing in the literal meaning of Chapter 16, Verse 18, of the Book of Mark:

They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.

They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.

Not long after my day of hunting snakes with Blodgett, a preacher of that faith had been bitten by the Timber rattler he was handling. The man refused treatment and died. That was in Kentucky, heart of Appalachia and the Timber rattler’s range.

Doug Blodgett’s interest in Timber Rattlers is scientific, not theological. He has been collecting data on the snakes for three years, now, helped by a grant from the Orienne Society, a non-profit dedicated to the preservation of endangered snakes around the world. Blodgett knows what there is to know about the Timber rattler and one of those things is … it is a creature to be respected. Not feared. Respected.

He reminds me, and his two assistants of this, as we are getting ourselves ready to leave the little clearing where we have parked and head up a long, rocky ridge line where he expects we will find snakes. He hands me a pair of snake proof leggings and talks while he is fastening a pair around his lower legs.

He reminds me, and his two assistants of this, as we are getting ourselves ready to leave the little clearing where we have parked and head up a long, rocky ridge line where he expects we will find snakes. He hands me a pair of snake proof leggings and talks while he is fastening a pair around his lower legs.

“These snakes are not aggressive,” he says. “They would much rather move away from a threat than stand their ground and strike. But if you surprise one, get too close, or provoke them, then they will strike.”

And the bite of one of these snakes, he says, is a serious business.

Serious, but rare. Very, very rare.

There hasn’t been a case of snake bite by a Vermont timber rattler since 2010 and that was the first in some fifty years. “Somebody drove up on a snake trying to cross a road,” Blodgett says.

No need to finish that story.

The man was taken to a hospital and treated with anti-venom. He recovered but probably, one thinks, still needs a brain transplant.

The leggings are a sensible precaution, of course. And, then, there are a few common sense rules. “I try,” Blodgett says, “never to put my hands on the ground. And if you do find a snake, stay calm. Don’t do anything to excite him.”

During these preparations, I remember how, as a kid, I would carry a little snake bite kit with me when I went into the woods. Today, we have cell phones. As with most medical emergencies, the best first aid is available at the nearest hospital and it is prudent to get there as quickly as possible and not waste time with amateur techniques.

We start in on a little trail with Blodgett in the lead. He walks briskly but not urgently and the three of us follow. The approach takes us through some low, wet terrain which doesn’t seem to interest Blodgett. Then, we begin to climb. The woods opens up into mature second growth with a surprising number of cedars mixed in with the usual beech, ash and maple. There are more rocks and rocky ledges and Blodgett slows the pace and begins to look, carefully, where he steps. He pauses frequently to look behind boulders and under overhangs.

The rest of us do the same.

There is actually a sort of pleasurable and stimulating sensation that comes over you—over me, anyway— when you are moving around in an area where you know there are snakes. Rattlesnakes, especially. You would like to think that you will be aware of the snake before he is alert to you. This means seeing him or, sometimes in the case of rattlesnakes, hearing him first. Rattlesnakes don’t just idly rattle. If you do hear one, then you are close and need to think about moving, once you have located the snake. I once heard a rattler, when I was bird hunting in Montana, before I saw him. The sound was absolutely unmistakable and it made me feel like my insides had turned to ice. It took me a few seconds—but not as many as it felt like—to locate the snake. He wasn’t quite in striking range. Maybe three or four feet from my leg. But he was coiled tight, puffed up, rattling vigorously and plainly meant business. I stepped out of range and then shot him with my shotgun. There was no question of doing harm to an endangered species. It was the third snake I’d seen that morning.

I didn’t expect to see—or hear—that many on the expedition with Doug Blodgett. We might not find any, he’d warned me. But knowing we were in rattlesnake country made me acutely aware. Shadows had become something more than just shadows. The dropped, dead branches of trees became shapes to be reckoned with. The sound of dried leaves, stirred by a vagrant breeze, became ominous.

Being alert and ready, however, doesn’t make it happen. We had searched the ridge line for two hours or so without finding any snakes when we took a break for lunch. We sat on a ledge of rock in a place open to sky and sun, looked over the countryside and talked idly about this and that. A lot of the conversation was about rattlesnakes and the very strong feelings they inspire.

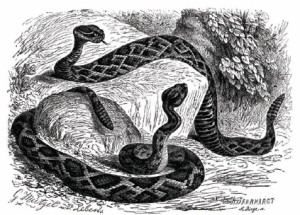

You need look no further for validation of that then the Latin name given to the timber rattler: Crotalus horrid us which combines crotalum, meaning “bell or rattle,” and horridus, for “dreadful”—which makes reference to its venom. Rattlesnakes are specific to the Americas so it is unsurprising that European settlers were impressed to the point of awe by them. And understandable that the Colonists should use the rattler on their flags along with the battle cry of “Don’t Tread on Me.”

Fear of the rattler led to an aggressive campaign against them.

“There was a bounty paid on timber rattlers in Vermont,” Blodgett says. “Right up until 1971.” He is stretched out on a slab of rock, admiring a hawk as it carves easy arcs in the sky above us.

“How much?” I ask.

“I believe it was three dollars. There weren’t a lot of people coming in to claim it. But over in New York it was different. There were snake hunters who knew where to go—where the denning sites were—and they would bring in a thousand, fifteen hundred snakes in a year.”

“That many?”

“Sure. There are still more snakes in New York than Vermont. And a lot more in Pennsylvania. Some parts of their range, they are doing well. Other parts, like Vermont, not so well. And in some parts of their original range, they are gone.”

“Wiped out by bounty hunting?”

“No,” Blodgett says. “Not really. It was caused by the usual thing. Loss of habitat. Competition with civilization. Plenty of snakes were killed by people who … well, that’s what they do when they see a snake. Particularly a rattlesnake. But they were also killed crossing highways”

But it does seem that the bounty hunters did kill a lot of snakes, especially in New York, where the most successful of the bounty hunters collected somewhere between fifteen and eighteen thousand snakes in less than two decades. The price fluctuated between three dollars and five dollars per snake.

That was enough to incentivize a little fraud and there were cases of people showing up at the county clerk’s office with a couple of hundred dead snakes and asking for their checks. One particular case involved someone from New Jersey. The locals were suspicious and asked the man to take them out and show them exactly where he had found and killed those rattlers. He drove them to a place that did, indeed, look likely. But the locals knew that it was no rattlesnake den; that no two hundred dead rattlers had come out of there. So the man did not get his money which seems, almost, a shame given the lengths he must have gone to, finding and killing and transporting all those snakes. There had to have been honest work available that paid better than that.

And it wasn’t always money that motivated people to seek out timber rattlers and kill them. Old timers would kill the snakes for their fat, which they would use to make … get ready for it, snake oil.

There was, in the 19th century, a brief craze for genuine snake oil of Chinese origin. It seemed to have some medicinal qualities. It was both swallowed and administered externally for arthritis, rheumatism and that family of aches and pains. The Chinese stuff was quickly bootlegged so that people who thought they were buying snake oil were getting something made from a variety of things, not always rendered fat, and certainly not always from snakes. Hence, the phrase, “Snake oil salesman.”

We have learned, lately, that snake oil—the real stuff—does, indeed, have medicinal properties. It contains the two types of omega-3 fatty acids most readily used by our bodies, more than salmon which is popular as a source of omega-3s. Reducing inflammation in muscles and joints is the main attribute ascribed to omega-3s. It is also believed to improve cognitive function, reduce blood pressure and cholesterol and perhaps even relieve depression.

If it can do all that, one thinks, then the snakes might find themselves pursued by a whole new set of enemies— health food fanatics.

Genuine rattlesnake oil was still made, fifty years ago, by people in Vermont who would soak the fat pockets that lined the snake’s cavity, then work the fat out of the membrane by hand, then heat it to extract the oil which they would then filter to make sure that it was pure.

Between that and the cash bounties, it is a wonder that any snakes survived.

I asked Blodgett if he had any sense of how many had.

“I suspect we’re down to a few hundred in Vermont. Most of them within a mile of two. I’m hoping we’ll find at least one on our way out.”

I am, too. I feel something like the avid birdwatcher who has come a long way hoping to add some rare specimen to his life list. I have something of a history with rattlesnakes. Where I grew up, along the Gulf coasts of Florida and Alabama, they were anything but rare, not especially secretive, and ranged in size from the aptly named Pigmy rattler to the Eastern diamondback, largest and most fearsome of all the rattlesnakes. They can grow to more than seven feet in length. Their venom is considered highly toxic and that much more dangerous for the size of the dosage if you should be hit by a really big one. I knew people who lost bird dogs to them. I never knew anyone who was bitten but heard a lot of stories about close calls, saw and killed a few, and once went out with some old boys on a rattlesnake roundup and caught one that went six feet. I can still remember every detail of the experience.

But I’d never seen a Timber rattler in the wild and, now, I badly wanted to. But since it is a rule of life that the more you want something, the less likely you are to get it, I figured as we packed up and started back down the ridge, that it wouldn’t happen today. If ever.

I followed Blodgett, who was still making his way carefully, looking around rocks, over blowdowns, under ledges. I did the same, though in the spirit of a formality. We weren’t, I thought, going to find any snakes. Wasn’t our day.

Then, Blodgett stopped and stiffened. Took a half step back and held up his hand in the universal signal for “Halt.” I did.

Blodgett motioned for his assistant who carried a snake hook and five gallon PVC bucket to join him. When he had, Blodgett signaled for me to come up.

Everything seemed to have gone suddenly very still.

I covered the twenty feet between us and was standing at Blodgett’s shoulder. He pointed to spot on a flat rock, in partial shade, four or five feet ahead.

At first, I saw nothing but shadow. Then, as I concentrated, a shape materialized out of the dark place on the ground. It was a darker black, inside the shadow that surrounded it, with the unmistakably sinuous lines.

There was our snake.

“Black phase,” Blodgett said. “Hard to see.”

“I’ll say.”

“Nice one, too.” Blodgett said.

Meaning it was four feet long, give or take.

I watched as Blodgett and his assistant carefully lifted the snake and put it, first, in the bucket and then in a long cylinder made of clear, hard plastic. Then, they did their science.

The snake is not one of those that Blodgett has previously implanted with a passive transponder. Nor does it appear to be infected with a fungus he is studying. So he weighs and measures the snake. Determines the sex. Female, as it turns out. Gets a fix, using a GPS, on the exact location where he found the snake. And records all this data in a notebook.

All this is of intense interest to Blodgett and understandably so. He is a scientist, doing field research. Me? I’m someone whose fascination with snakes leans more in the direction of the inchoate and the poetic.

So while Blodgett and his assistant discuss their findings and record them, I watch the snake which they have released make its slow and elegant way back to someplace that she knows she wants to go. The movement is beautiful in a sort of sinister way, as is the snake’s coloration, and something about the combination—the whole package—stimulates a shudder that passes down my back and through my body.

It isn’t fear. I’m in no danger. But some things, when you see them in the wild, remind you that the world is a marvelously wild, mysterious and, sometimes, dangerous place.

And that the state of Vermont would be a lot less interesting without rattlesnakes. ◊

Geoffrey Norman writes frequently for STRATTON MAGAZINE and other publications, to include THE WEEKLY STANDARD MAGAZINE.