By Andrew McKeever

Photography By Hubert Schriebl

Silence.

Maybe it’s the rarified air at 3,848 above sea level, or the sweeping panoramic views at all points of the compass. “Awesome” is one mightily overworked word in modern lexicon, but here it fits.

“Here” is the St. Bruno Scenic Viewing Center at the end of the Skyline Drive of Mt. Equinox. You get there by driving five miles or so up the paved and often winding road, which is long enough to start in Sunderland and end in Manchester. It offers some potentially exciting hairpin turns along the way to go with one of the steeper overall inclines of comparable scenic mountain drives in New England. Make sure your vehicle’s brakes are up to the task for the return trip. Or stay in low gear. Or both. As the saying goes, getting there is half the fun. Or, it’s about the journey, not the destination. Take your pick.

But the destination is pretty cool.

The St. Bruno Scenic Viewing Center is nearly 4,000 feet above sea level. From this lofty perspective, you can see a lot.

Once you do arrive at the mountaintop, the silence greets you. Even if you happen to arrive with a group, or the parking lot in front of the viewing center has more than a couple of cars, there’s a muting effect about the place that suppresses talk and chatter while your mind absorbs the spectacle. The predominant sounds are the breezes blowing through the trees. Time is suspended, as you look, probably first to the right, or east, at the long finger of the “Vermont Valley,” the

cleft left behind by the retreating Ice Age glaciers millennia ago which shaped the region’s topography. On a clear day you can see down to the Berkshires in Massachusetts. On the other side of the valley stand the opening foothills and ridges of the Green Mountains—no further introduction needed, right? Beyond lies the Vermont heartland.

Look northwards and the rippling mountains and ridges roll on towards Killington and eastwards across the state’s central spine. At the summit you are still in the Taconics—on the highest peak in the long range of mountains that continue far to the south in New York. You are also at the highest point in Bennington County, and the 12th highest in all of Vermont. Only Stratton, Pico and Killington’s two peaks are taller among the mountains in the southern half of the state.

At the summit you are still in the Taconics—on the highest peak in the long range of mountains that continue far to the south in New York.

Turn around, and look to the left of the viewing center, and an even more remarkable vista unfolds. An endless rolling sea of green forested mountains unfolds, starting with the plunging escarpment of the western face of Equinox, marked only by a strangely shaped blockish building that you already know is the monastery of the Carthusian order, assuming you stopped in the flattish “saddle” between the summit of “Little Equinox” and the viewing center and read the helpful plaque at the “monastery view” posted there. Otherwise, it’s all mountains and rolling hills as far as the eye can see deep into New York— a true bird’s eye view.

Not far from where you would have stood to absorb the information on the monastery view plaque, along the spur of a ridge that trails away on “Little Equinox,” is the site of where one of the nation’s earliest attempts at renewable energy—wind energy— didn’t make it.

One turbine, smallish by today’s standards, was installed there in 1981 and three more added the following year. But they suffered from mechanical issues and all were shut down within a few years and the turbines removed. A second try came in the early 1990s, when Green Mountain Power, now the state’s largest electrical utility, constructed two more turbines, which ran and produced electricity until 1994 before they too were removed. An older Cold War era radar tower is still there—now used as a radio transmitter by the Vermont State Police. Another tower houses the transmitter for WEQX, a popular contemporary music radio station based in Manchester. Vermont Public Radio also has a transmitter there.

Outwardly there may be silence, but there’s still a lot of communication going on, apparently.

But quietude is important to the monks of the Carthusian order, whose defining characteristic is, after all, the vow of silence the monks make when they enter the order. It was one reason they were leery about the most recent effort to place a new generation of wind turbines atop Little Equinox, says Frank Dyer, the manager of the mountain for the Carthusians.

“They don’t want noise, and the silence is important to them,” he says, adding that concerns about the possible sounds generated by the rotation of the turbines were troubling to them back in 2005, when the proposal was a prominent local issue.

The monks may want and take vows of silence, and want to be left alone to pursue their individual and monastic journeys, but on the other hand they also believe in keeping the mountain open and accessible to the general public, Dyer adds. Within bounds, of course. The eastern, or “front” part of the mountain, the side that faces the Green Mountains, is where most people enter to take in the views. The back, or western side, where the monastery is located evolves into thinly populated and densely forested Sandgate, more the monks’ own backyard. While trails and former roads may still crisscross the area, dedication plus curiosity is required—though not necessarily encouraged if you cross into part of the 7,000 acres the Carthusians hold title to.

“The monks feel there’s a lot spirituality in the mountains, in the views, the nature, and they want to share that,” Dyer continues. “It fits their needs perfectly, and that’s why we try to keep the front side of the mountain the more public side, and leave that divide, so they don’t have to hear the cars going by.”

That desire to keep the mountain accessible led to the construction, completed in 2012, of the 2,200 square-foot St. Bruno Scenic Viewing Center, named after the founder of the Carthusian order. It was built with environmental factors in mind, and is powered with solar energy and heat pumps; almost, if not quite, a “net zero” building, Dyer says.

The Carthusians’ Equinox home is the only North American monastery of the order, whose vow of silence is their pathway to the contemplation of the divine.

The outwardly functional and simple structure signals journey’s end for travelers up the Skyline Drive. The drive has been a fixture of the Vermont tourism experience since 1947 when it was completed under the direction of Dr. Joseph Davidson. The former Union Carbide executive and board chairman owned the mountain before willing it to the Carthusians, a 930 year-old Catholic monastic order. Their Equinox home is the only North American monastery of the order, whose vow of silence is their pathway to the contemplation of the divine. It’s fair to say that no other individual of modern times remotely comes close to leaving a bigger imprint on the mountain than Davidson, and his legacy lingers on decades after his death.

The viewing center had been under contemplation since at least 2006, Dyer says, when attempts to keep the former landmark Skyline Inn—a restaurant and lodging establishment first built in the early 1950s and closed since 2001 or so—were abandoned and plans made to use the site as a viewing area, complete with enclosed rooms adorned with plaques describing the history of the mountain along with tables for sitting, snacking or soaking up the views. There’s also a small, not-quite-fully sound proofed, but well muffled, meditation room. There, a visitor can find a deeper silence, to read, contemplate or just sort things out.

“The monks didn’t want an inn, but they wanted a place for people to have that experience,” Dyer says.

Not far from where one sits in the meditation room, along a trail that eventually leads to Lookout Rock, one of the several remarkable viewing spots overlooking Manchester and a short distance from the actual summit of the mountain itself, is a small monument to Mr. Barbo, Dr. Davidson’s faithful dog, a Norwegian elkhound and Siberian husky, to whom he was devoted, and vice versa. His death at the hands of a hunter was one of those turning point moments in the mountain’s history. Up until then, in 1955, the mountain was open to hunters, but that November Mr. Barbo was fatally shot — possibly in self-defense — by a hunter. Despite all efforts by Davidson to find out his identity, the hunter never confessed or was turned in by anyone. In response, Davidson posted the mountain, and closed it to trapping and hunting. He hired sheriff’s deputies to patrol and enforce the ban, as Tyler Resch, a former editor of the Bennington Banner and now a curator at the Bennington Museum, recalled in “Deed of Gift,” his book about the Putnam Memorial Hospital, as the Southwestern Vermont Medical Center in Bennington used to be known as. Davidson was also an important figure in the hospital’s history, serving as chairman of the hospital’s board of directors for several years during the 1960s. He passed away in 1969 while a patient at the hospital, and one of his last acts was to transfer management of the mountain property to the Carthusians.

Mount Equinox had first been explored and navigated by Captain Alden Partridge. Partridge, whose father fought in the Revolutionary War at Saratoga, was an early superintendent at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, and a founder of Norwich University, which has a strong linkage to the military to this day.

Partridge, a scientist with a fascination for barometric observation, calculated the height

of the mountain with remarkable accuracy—he was only off by about 40 feet using the crude instruments of the day.

According to Tyler Resch, Partridge, an avid hiker and an early proponent of the virtues of physical fitness before that was fashionable, led a team of cadets from Norwich on a hike over to Manchester, reaching the mountain in mid-September of 1823. This is the first recorded ascent to the peak, and where Partridge, a scientist with a fascination for barometric observation, calculated the height of the mountain with remarkable accuracy— he was only off by about 40 feet using the crude instruments of the day. Since they arrived roughly around the time of the autumnal equinox, “Equinox” it became, legend says.

More likely it was a slight corruption of the Native Americans known as the “Ekwanok” or sometimes the “Akwanoks,” says Resch. Either way, Partridge had opened the door.

The land around the mountain of course was already widely in use by local residents of the day for grazing and logging.

Tribes of Native Americans certainly inhabited the area before the earliest European and colonial settlers arrived in the middle of the 18th century, but they left behind few visible traces around and about the mountain, says Shawn Harrington, of the Manchester Historical Society, adding that a comprehensive study has never really been done.

Until Davidson’s arrival, the mountain remained largely undeveloped, aside from its use for grazing, pastureland and logging. Davidson began acquiring property on the mountain incrementally, eventually owning about 7,000 acres. He was interested in hydropower, and built an artificial lake, known as Lake Madeleine after his wife, and today the monks and the mountain produce enough electricity to sustain the monastery, the viewing center and the rest of their needs, with enough left over to sell to others, such as Burr and Burton Academy, which buys some of it as part of a green energy program for the school. He also pondered building a ski area on the mountain but eventually abandoned the idea. A restaurant and a 27-room inn was eventually constructed— named the Skyline Inn, of course— which survived for nearly 50 years before it evolved into the present day viewing center.

Courtney Mutz Callo, now an administrator at the Long Trail School in Dorset, remembers growing up there as a child when her parents leased the inn from Dr. Davidson from 1964-76.

“Thunder and lightning storms were intense but the beauty was incredible,” she says. “We did not have a lot of problems with wild animals, because it was too high.” Other than porcupines, which liked to chew on the salty, wooden undersides of cars parked overnight, she remembers.

Getting up and down the mountain could be challenging at times, and communication with the monks, other than the two designated contacts who are free to speak to members of the outside world, could be “tricky,” she says. Somehow, it worked.

Her parents had to meet with the monks from time to time, but her mother was not allowed in the monastery, except for one small room. One day, Courtney got inside and saw some of the cells, she recalls.

“That was a huge issue,” she says with a chuckle now.

Delivery trucks would unload supplies at the tollhouse at the base of the mountain, and her father would then make numerous trips back and forth to bring them up to the Inn. It was grueling and draining, but her father loved it. Eventually though, the offer of a full-time job at the more accessible Bromley Mountain proved impossible to resist, she says.

“It was an amazing place to grow up,” Courtney says.

Eventually the building fell out of compliance with state codes and was shut down, leading to its eventual conversion to a visitor and viewing center. But the summit area has stayed pretty much the same now as it was back when she was growing up, she says.

There’s more to do at the viewing center than just look around—several hiking trails bisect the area, including the one to Lookout Rock. The “Blue” hiking trail starts at the back of Burr and Burton, and is part of the network of trails maintained by the Equinox Preservation Trust. More than 900 acres on the eastern slopes of Equinox are owned by the Equinox Resort in Manchester Village, donated through conservation easements to the Vermont Land Trust to protect its natural state. This trail snakes its way all the way up to the top. So if you don’t feel like driving down the mountain the way you came, there is an alternative, assuming you have proper footwear.

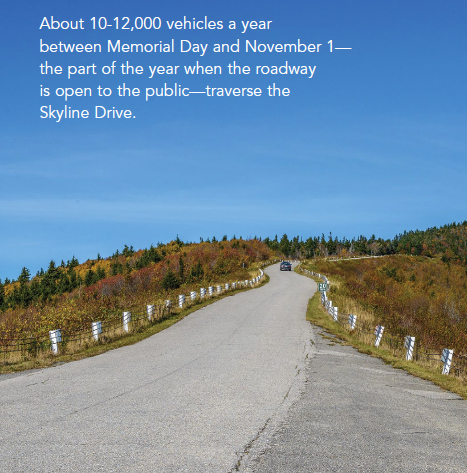

About 10-12,000 vehicles a year between Memorial Day and November 1— the part of the year when the roadway is open to the public—traverse the Skyline Drive.

Once you take your leave of the summit and arrive back at the base of mountain, the small tollhouse gift shop is worth a look. It is there that the tokens to allow you to drive up in the first place are purchased. The shop also sells books and souvenirs.

About 10-12,000 vehicles a year between Memorial Day and November 1—the part of the year when the roadway is open to the public—traverse the Skyline Drive, Frank Dyer says, noting there has been a sizable increase in motorcycle traffic in recent years.

An annual vintage sports car rally still takes place each year, joined a few years ago by a bicycle race that benefits Lyme disease research. All the activity, including the hydropower program and some logging, helps pay for the costs of keeping the road open and maintaining power lines—the mountain aims to cover its costs and pay its own way, Frank Dyer says.

“There’s never an abundance of spare cash,” he says. “We attempt to break even. It’s a balancing act.”

But all that helps keep the road open and the mountain accessible, which is one of its special characteristics, says Shawn Harrington of the Manchester Historical Society.

“You can drive up it, hike to the top of it, and see man-made lakes and dams; hydro generation and a large monastery,” he says. “It’s been developed, but it maintains its serenity.”

And, by and large, its silence, which lingers upon returning to the valley and Route 7A. It takes a while to reconnect to the “real” world after your encounter with the sacred, serene and silent one. ◊

Andrew McKeever, a writer from Shaftsbury, is a frequent contributor to Stratton Magazine.