Crowds at the U.S. Open Snowboarding Championship at Stratton Mountain in 2005.

Vermont Snowboarding Turns 40

By Gayle Fee

Photography By Hubert Schriebl

In the beginning, there was snurfing.

Christmas, 1965: Sherman Poppen cross-braced two Kmart skis together for his children to ride and called it the Snurfer. But if snowboarding began in Poppen’s Michigan garage, it came of age—and was catapulted to a global sensation—in Vermont.

So let’s begin our story in Londonderry where the father of modern-day snowboarding, Jake Burton Carpenter, opened his first store in a barn in 1977. Mimi Wright was his first employee.

“In 1977, nobody was snowboarding,” she said. “Jake was a surfer from Long Island and he had the idea that he could develop something better than the Snurfer.”

Burton produced his first snowboards in 1978. They were simple wooden planks with a rubber mat, a rope on the front, and straps meant to harness anything from work boots to sneakers. But those first “snow surfing” boards had something that has endured for 40 years: the famous Burton mountain logo, designed by Mimi.

“We only produced 300 boards that year and they didn’t all get sold,” she said. “It was a big deal when we sold one.”

By the summer of ’78, business was so bad, Burton had to lay off Mimi and his other two employees. He moved the business to Manchester and persevered.

“Jake was an amazingly driven person with a dream,” Wright said. “Nobody believed in him. He was out there fighting the battle by himself.”

Burton would hike the hills facing Vermont’s roadways and carve S curves down the slopes to draw attention to his new invention. He befriended Emo Henrich, the legendary ski school instructor at Stratton Mountain, who would critique the boards and help with the design.

“I’m sure Emo was a good in for Jake at Stratton,” Wright said. “But there was a lot of resistance to snowboarding at the time.”

Some resorts feared liability issues. Others simply didn’t want neon-clad teenagers bothering their posh skiing clientele. In the early 1980s, a campaign to get mountains to accept riders was launched, and in 1983, Stratton Mountain became the first major resort to allow snowboarding.

“It had a lot to do with the courage of the management at the time,” said Stratton Mountain president Bill Nupp. “Being first is a big part of who we are.”

At the beginning, it wasn’t all easy sliding. But despite the sometimes testy relations between skiers and riders, the Stratton bosses believed the camps could peacefully co-exist because they were connected “at a fundamental DNA level… brothers in arms on the hill,” Nupp said.

Former competitive snowboarder Steve Hayes, now 50, remembers “poaching” Stratton with a group of pals in the late ’70s and early ’80s, taking off from a friend’s trailside condo and shredding the slopes until the ski patrol chased them off. But in 1983, Hayes and his brother became the first two snowboarders officially certified to ride the mountain.

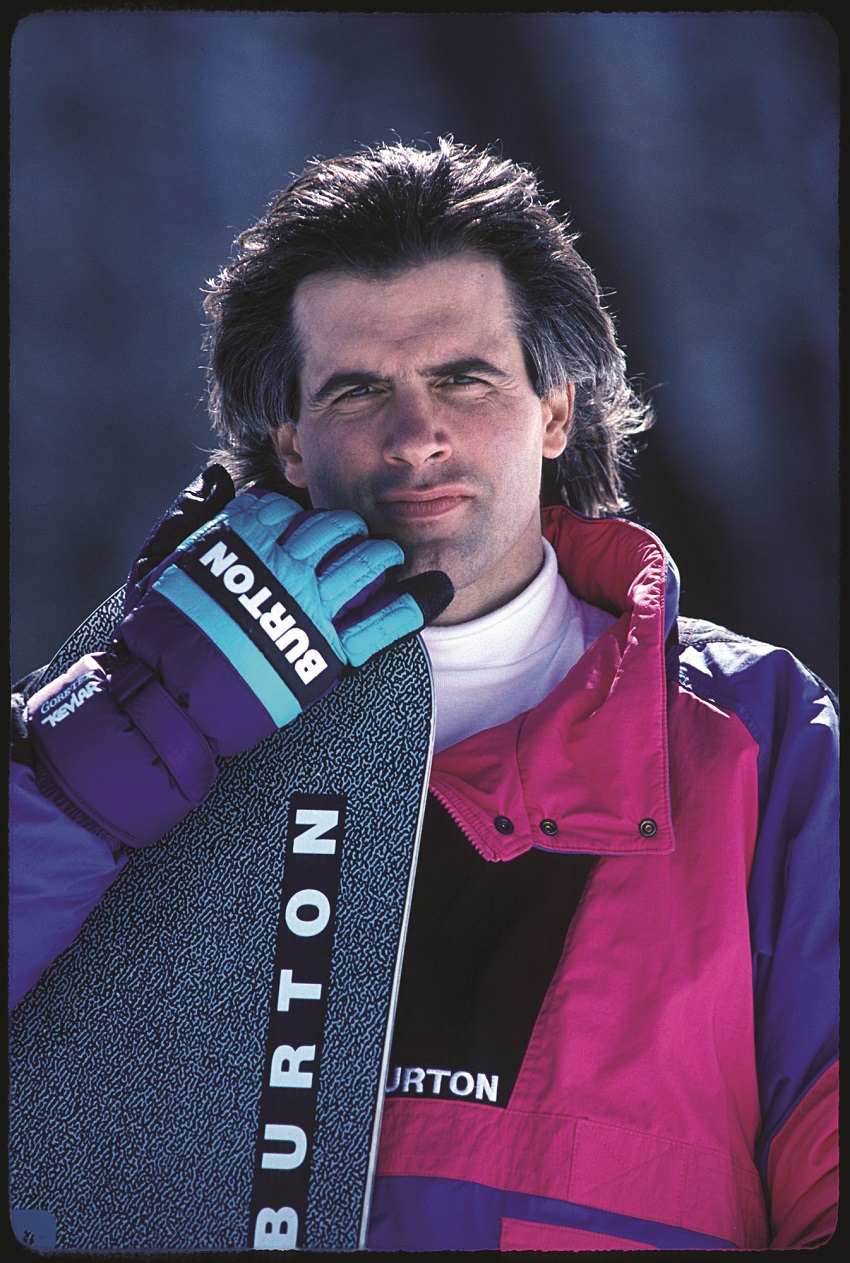

Jake Burton, 1990.

“This one day we rode down and Jake Burton and (mountain manager) Paul Johnston were at the bottom of the Villager lift. They told us we had to be certified or we couldn’t go,” Hayes recalled. “I had been snowboarding for four years by then and had the typical punk attitude. But they quickly reassured me that they were working on a program and they would appreciate it if we would follow the rules. So we passed the test and got certified and then we were hired by Burton to perform certification tests for other riders.”

Many of the boarders who were certifying other riders also became instructors at the country’s first snowboarding school at Stratton Mountain. Hayes, who was a ski racer at nearby Stratton Mountain School, became a member of the very first Burton snowboard team and as the sport grew in popularity, he began to have more opportunities as a competitive snowboarder than as a skier.

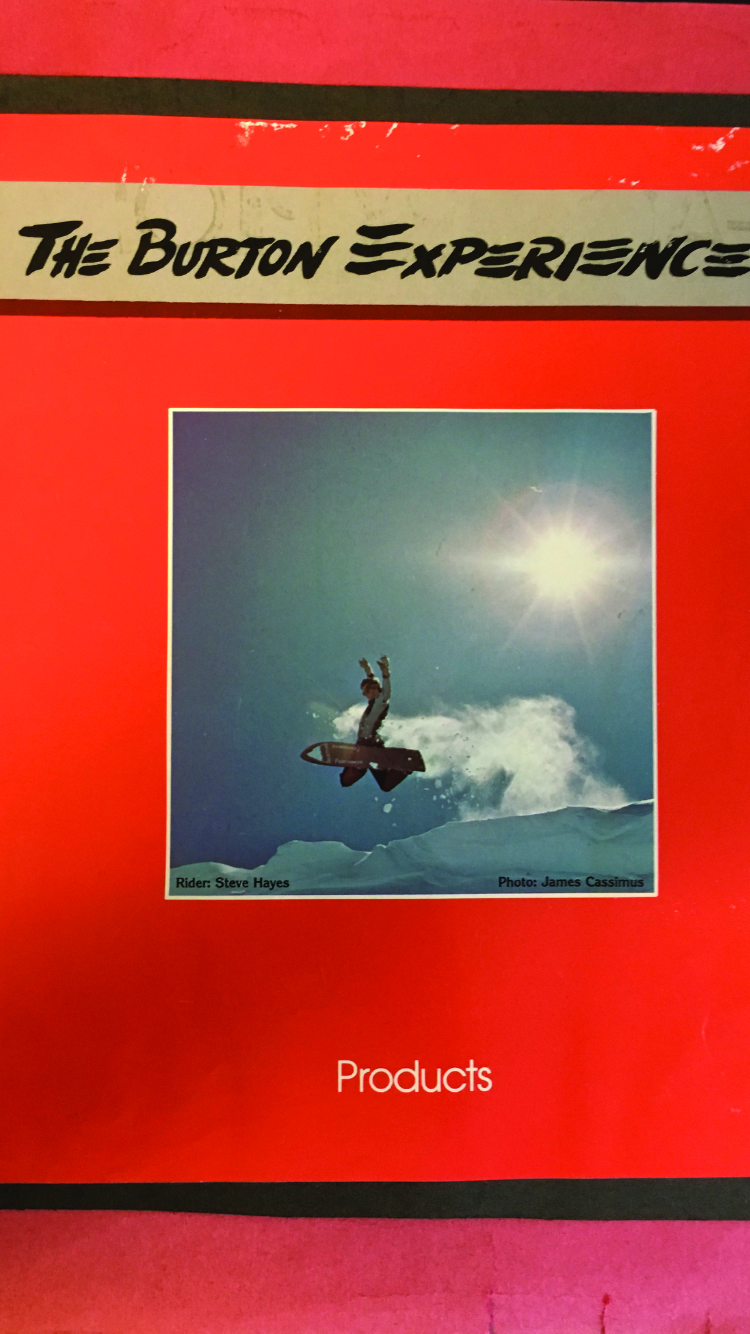

“Burton products began arriving at my SMS dorm room and all of a sudden I was a rock star,” he recalled. “I got to fly out to California for the SIMS World Championship. I flew on a private jet to Arizona to do a commercial for Swatch watches where we snowboarded down the sand dunes in Yuma. I made the cover of the Burton catalog.”

Early Burton catalog with Steve Hayes on the cover.

But at the time there was no snowboard program at Stratton Mountain School, where one of the coaches would loudly proclaim in a German accent “snowboarders are losers!” so Hayes sought the advice of his ski coach.

“He said, ‘It looks like you are going more places as a snowboarder than a skier. But I never told you that!’”

In 1985, Burton launched the U.S. Open Snowboarding Championship at Stratton Mountain where it ran for 30 years and evolved into one of snowboarding’s most prestigious events, bringing the sport’s top athletes and coaches to the area including two-time Olympic gold medalist Shaun White.

“I knew my future was ahead in snowboarding,” Hayes said. “But my parents forced me to go to college. My mother said, ‘Snowboarding will never be an Olympic sport; you’ve got to stay in school.’ Thankfully for me, I did.”

An injury in 1995 ended Hayes’s competitive career—three years before snowboarding finally did become an official Olympic sport.

“It was kind of harsh for me because, growing up, I always wanted to be an Olympian. But I do consider myself a pioneer of the sport and believed I helped it gain Olympic acceptance,” said Hayes who competed in the New England Cup—the first snowboarding event on the East Coast—and supported the effort to draft the first set of snowboard competition rules.

Local favorite Mark Heingartner competes in an early

snowboard FIS race at Stratton.

The first snowboard contests were modeled after FIS ski races with downhill, slalom, and giant slalom events. The invention of the machine-made half pipe in 1992 and leaps in snowboard design kicked off a new era for the sport with riders taking their acrobatic inspiration from skateboarders such as Tony Hawk. Londonderry’s Ross Powers, the 2002 Olympic half pipe gold medalist, started at Stratton Mountain School in 1993, the first year SMS offered an official snowboard program and coach.

“A lot of the tricks came from skateboarders,” Powers said. “They were the first to build ramps and jumps. But with snowboarding you could take it to the next level. You could go faster and higher and you had softer snow to land on when you crashed.”

Ross Powers, 1995.

In 1998, snowboarding made its Olympic debut at Nagano, but true to its roots, the sport’s first foray at the Winter Games was not without controversy. The world’s top rider, Norway’s Terje Haakonsen, boycotted the games in a dispute over the rules, and snowboarding’s first gold medalist, Canada’s Ross Rebagliati, tested positive for trace amounts of marijuana. Stratton Mountain’s Ross Powers scored a bronze at the Nagano games.

But it was the United States men’s halfpipe sweep at the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City that cemented snowboarding’s place in America’s heart. Powers won gold, Danny Kass, who trained at Okemo, won silver, J.J. Thomas took bronze, and Vermont became the epicenter of the snowboarding universe.

Since 1998, Vermont—and especially Southern Vermont—has sent dozens of snowboarders to the Winter Games, including gold medalist Kelly Clark, gold medalist Hannah Teter, silver medalist Lindsey Jacobellis, and bronze medalist Alex Deibold.

Shaun White at the U.S. Open in 2004, held at Stratton.

“There’s a rich history of snowboarding at Stratton, it’s awesome to say. It’s the epicenter,” Nupp said, adding that having so many elite snowboarders call the area home is “kind of like the light on top of the Christmas tree.”

From its inauspicious beginnings in Londonderry, snowboarding has become a worldwide phenomenon, and the halfpipe competition—celebrating its 20th anniversary in February in PyeongChang— continues to be one of the biggest draws in the Winter Games. And it all started right here in Vermont thanks to a man with a single-minded vision and some fearless local athletes who dreamed of flying through the air and landing on the snow, and thus created a whole new sport.

A Monument to Londonderry’s Snowboarding Past

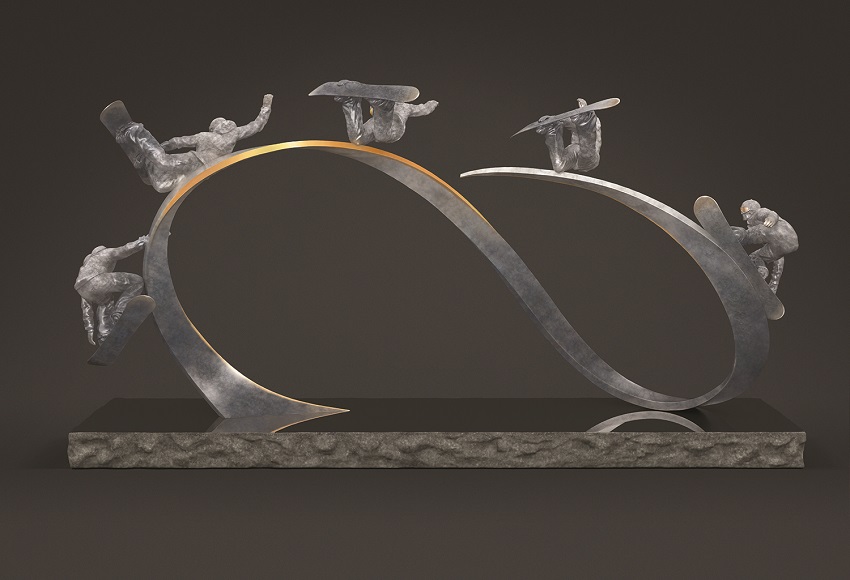

Modern snowboarding began 40 years ago in a Londonderry barn, and now a Colorado sculptor wants to memorialize the region’s half-pipe legacy with an ambitious piece of public art he’s calling the Snowboard National Monument.

“There’s such a tremendous amount of snowboard history in the Londonderry area,” said Loveland, Colorado artist Jason Dreweck. “I really want to help reveal this to people with this piece.”

Dreweck and the Londonderry Arts and Historical Society just launched a $1.3 million campaign to fund the creation of a 30-foot-long cast bronze sculpture depicting gold medalist and Londonderry native Ross Powers’ massive Method air grab at the 2002 Olympics. Dreweck hopes to install it near that Londonderry barn, the site of the original Burton Snowboards.

“I just feel so passionate about the entrepreneurial perseverance and grit in this whole story,” Dreweck said. “And I wanted to capture that with this piece. I wanted to show what it takes to ride the ups and downs and kind of take that leap of faith that snowboarders and entrepreneurs both take.”

To fund the installation, Dreweck is creating 111 smaller sculptures—the number was chosen in honor of Burton Snowboard’s first location at the intersection of Routes 100 and 11. Dreweck, Powers, and Jake Burton Carpenter all collaborated on the design and will sign the finished pieces, which will be sold for $14,200 each to fund the bigger project.

“To have this modeled after my 2002 Olympic Method is really cool and a real honor,” Powers said. “I hope this can happen. It would be awesome for Londonderry.”

Stratton Mountain has already purchased No. 1 in the series of smaller sculptures and Burton has ordered No. 13 but Dreweck said he has no idea how long the fundraising will take.

“It’s definitely a huge undertaking,” he said. “I don’t know that anything like this has ever been done before and by that I mean all aspects of the project from the artist working with a pioneer of the sport and the gold medalist along with the unique funding concept. I think in the world of fine art, this experience is really incredible.”

For more information on the sculpture, go to snowboardnationalmonument.com.