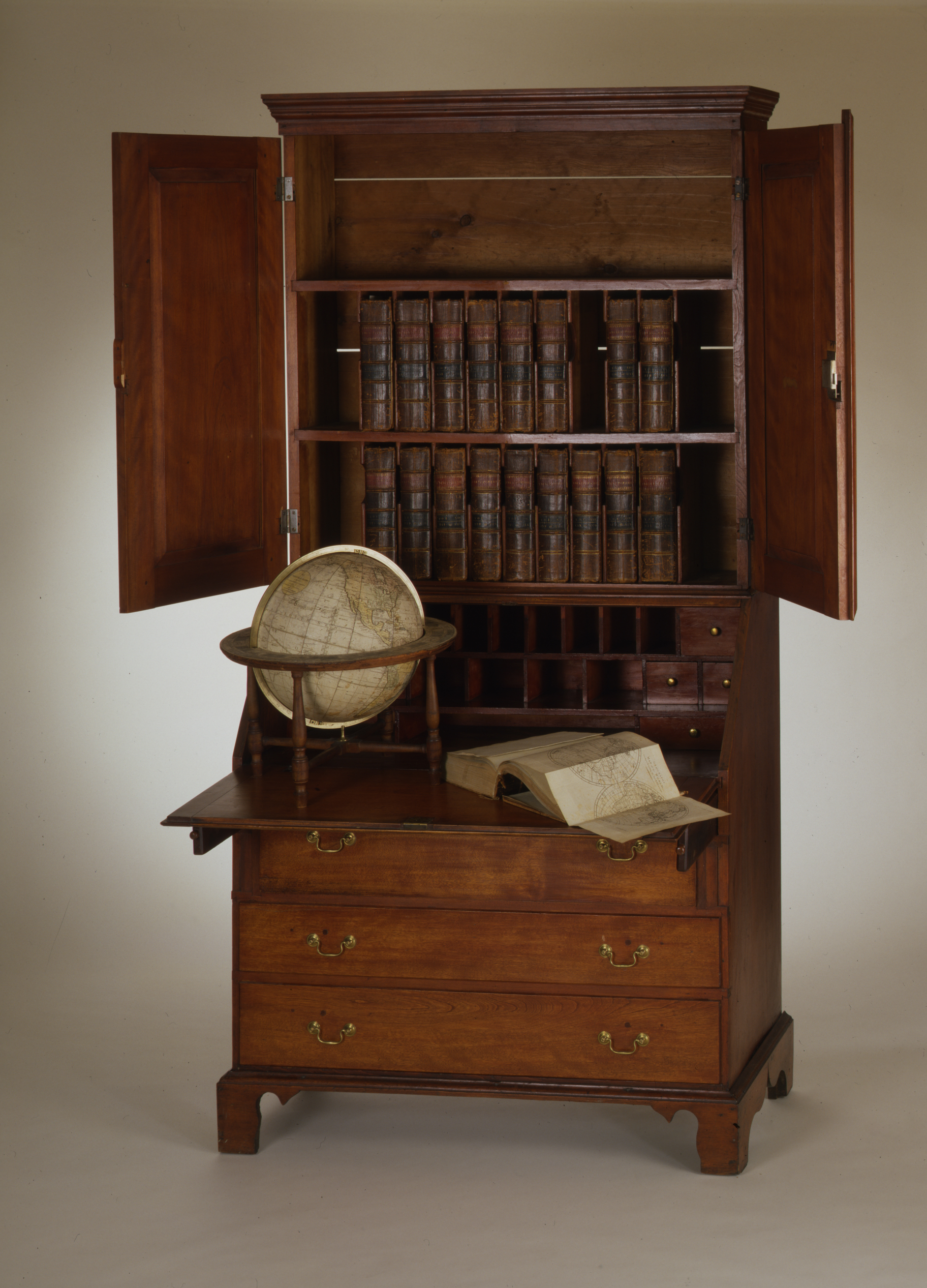

Desk and Bookcase owned by James Wilson, ca. 1800

Unknown maker

Cherry, pine

Gift of Mrs. Donald Spencer

Bennington Museum is pleased to announce the opening of the Early Vermont Gallery. A permanent installation with rotating textiles, this gallery presents life in Vermont from the time when the earliest European settlers arrived in 1761 with only the bare necessities to the early 1800s when Vermont craftsmen achieved a level of sophistication rivaling Boston and New York. (1760s to early-1800s) Explored through stories and vignettes, this gallery showcases over 85 major pieces and smaller items from the Museum’s extensive historical collection of over 30,000 objects. “We hope that these objects will serve two distinct purposes. First, to share with the public the deep, rich collection we maintain here at the Museum; Second, to tell fascinating stories of the early life in Vermont.” states Robert Wolterstorff, Executive Director of the Bennington Museum. Housed in the former Decorative Arts Gallery, this 866 square foot space includes beautiful pieces representing the sophistication achieved not long after Vermont was first settled.

The Background

Vermont was one of the last areas of New England to be inhabited by Europeans. This land was claimed by both the colonies of New York and New Hampshire, but New Hampshire’s royal governor, Benning Wentworth, began issuing grants for towns in 1749, hoping to realize large profits on the sale of the “New Hampshire Grants.” The established New England colonies were running out of cheap, available land, and the New Hampshire Grants were quickly bought up. New York reasserted its claim of ownership in 1763, with the support King George III, and in 1777, leaders in the New Hampshire Grants, including brothers Ethan and Ira Allen, declared the region an independent republic. They called it Vermont, taken from the French words for “Green Mountains.” In 1791 Vermont joined the Union as the fourteenth state.

Terrestrial globe, 1810

James Wilson (1763-1855)

Bradford, Vermont

Purchased with funds from the Hall Park McCullough Fund

Growth and Prosperity

The earliest piece in this exhibit is a simple six board chest made by Peter Harwood around 1762, when his family moved to Bennington. It represents the type of useful furniture needed on the frontier. The Harwood family prospered, and in 1769 Peter built a larger two-story frame house. Like other settlers, they acquired finer furnishings, and recreated the familiar culture they had been accustomed to in their hometowns. A fine example is the sophisticated corner cupboard and tea table Jedidiah Dewey made for his son Eldad’s new house in 1769. Corner cupboards were built into the most public room of the house, and used to store and display fine china, silver, pewter, and other pieces necessary for entertaining. Tea drinking in particular was a highly ritualized social custom, and owning the furniture and accoutrements associated with serving tea showed off a family’s wealth and social status. “The fact that Bennington homes had fancy cupboards and tables specifically dedicated to the social custom of drinking tea less than a decade after the town was settled speaks to the rapid progress the settlers made.” states Callie Raspuzzi, the Museum’s Registrar and curator of this gallery. “It was a time of enormous opportunity in Vermont, but there was also enormous risk. Many families were never able to afford the fine furnishings seen throughout this gallery.”

Musical tall case clock, ca. 1810

Movement by Nichols Goddard (1773-1823)

Rutland, Vermont

Mahogany and white pine with mahogany veneer and light and dark wood inlays

Museum Purchase

By 1810, Vermont was one of the fastest growing states in New England. No longer an isolated frontier, Vermont artisans achieved a level of sophistication that rivaled urban centers of Boston and New York. In Rutland, Nichols Goddard created musical clocks that were masterpieces. The musical tall clock on view represents the height of sophistication available in the United States in the early 1800s. “Very few Americans owned clocks of any sort at this time,” states Raspuzzi, “and musical clocks were certainly a sign of a refined home. None were more mechanically complex, or beautiful than this one.” A set of ten bells and hammers play seven tunes which are listed around the dial of the face. The movement, featuring a day of the month wheel and moon dial with a depiction of a burning ship, was complex and would be the high point of a clockmaker’s career, achieved by only a small fraction of artisans. With its careful sequence of matched mahogany veneers and inlays, the case is a masterpiece in itself derived from high style New York City and New Jersey examples.

Corner cupboard from the Eldad Dewey house, Bennington, Vermont built in 1769

Attributed to Jedidiah Dewey (1714-1778)

White pine

Gift of Charles Dewey

Another object in the gallery that represents the early accomplishments of Vermonters is one of the first globes ever made in the United States manufactured by James Wilson of Bradford. A farmer with no formal education, Wilson purchased a set of Encyclopedia Britannica and proceeded to teach himself geography, astronomy, mathematics, and cartography in order to achieve his goal. Beautiful furniture was created by George Stedman of Windsor who crafted complicated “bombe” front chests. This particular chest was a difficult form to make, since each drawer had to be bent and shaped to match the curved front of the chest. The form originated in France, and was popular in the Boston area in the late 1700s. This chest is one of only six known Vermont-made examples that exist in public collections. Both of these examples points to the determination and creativity of early Vermonters.

The portrait of Julius Norton with a flute and piano might raise questions about music and its place in the home. An accomplished musician, Norton played the flute, violin, and piano. His valuable piano reflected the family’s wealth earned from their successful pottery business. The Norton family’s neighbor Hiram Harwood was also a musician and noted entertainments in his diary (in the Museum’s collection) from formal dances held in a local ballroom to small groups of friends dancing in the kitchen. Along with dancing, alcohol flowed freely. On view in the Early Vermont Gallery is Orsamus Merrill’s flute and wine chest which would have been used together.

Julius Norton, ca. 1840

Erastus Salisbury Field (1805-1900)

Bequest of Mrs. Harold C. Payson (Dorothy Norton)

The Erie Canal’s Impact

In many cases through creativity and innovation came prosperity and growth to many upon who settled in Vermont. But this growth would come to a grinding halt in 1825 with the completion of the Erie Canal, which opened up the West with its flat, easily tillable farmland. Thus began a gradual depopulation of Vermont that has continued into the 21st century. Today’s quaint villages and forested hills give little evidence of the early “boom” years. By the twentieth century, Vermont had developed an appeal to tourists as a place that time forgot. The Museum’s “Early Vermont” gallery reminds us of the bold and innovative Vermonters who prospered during the state’s formative years.

About the Museum

Bennington Museum is located at 75 Main Street (Route 9), Bennington, in The Shires of Vermont. The museum is open daily June through October, 10 am to 5 pm. It is wheelchair accessible. Regular admission is $10 for adults, $9 for seniors and students over 18. Admission is never charged for younger students, museum members, or to visit the museum shop. Visit the museum’s website www.benningtonmuseum.org or call 802-447-1571 for more information.